Ever since a young Bill Gates grooved on stage at the launch of Windows 95 — alongside Steve Ballmer, his eventual successor as CEO of Microsoft — we’ve become accustomed to seeing tech entrepreneurs in the public eye.

Many have become household names, their stories celebrated in best-selling books, their personalities portrayed by Hollywood stars in hit movies.

But behind the headlines, how well-known are the individuals who run the world’s most successful tech companies today? Not so much, it turns out.

We recently surveyed respondents* in the United States about the reputation of 12 tech giants and their founders or CEOs — and found out the following:

Our first question sought to determine whether respondents could correctly select the name of the company’s founder or CEO from our list.

In most cases, less than half could.

The exceptions? Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg.

For the tech titans in question, this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Invisibility is a benefit, not a bane. Most CEOs or chairmen probably want to keep their “personal brand” — such that it exists — out of the picture.

To the extent that they want to be “visible”, it’s with select stakeholders (media, investors, legislators) about select issues (corporate strategy, financial growth, regulation).

As for the outliers — Musk and Zuckerberg — they scarcely need explaining. The former continues to be, as tech writer Nick Hilton put it, “outspoken, irreverent and public facing”.

Indeed, whether it’s launching Teslas into space or torpedoing Twitter’s share price with a single tweet, Musk is rarely out of the limelight. Zuckerberg, meanwhile, has long been seen as “the enfant terrible of Palo Alto”, his story immortalized by Hollywood.

Our next question asked respondents to evaluate the companies in question.

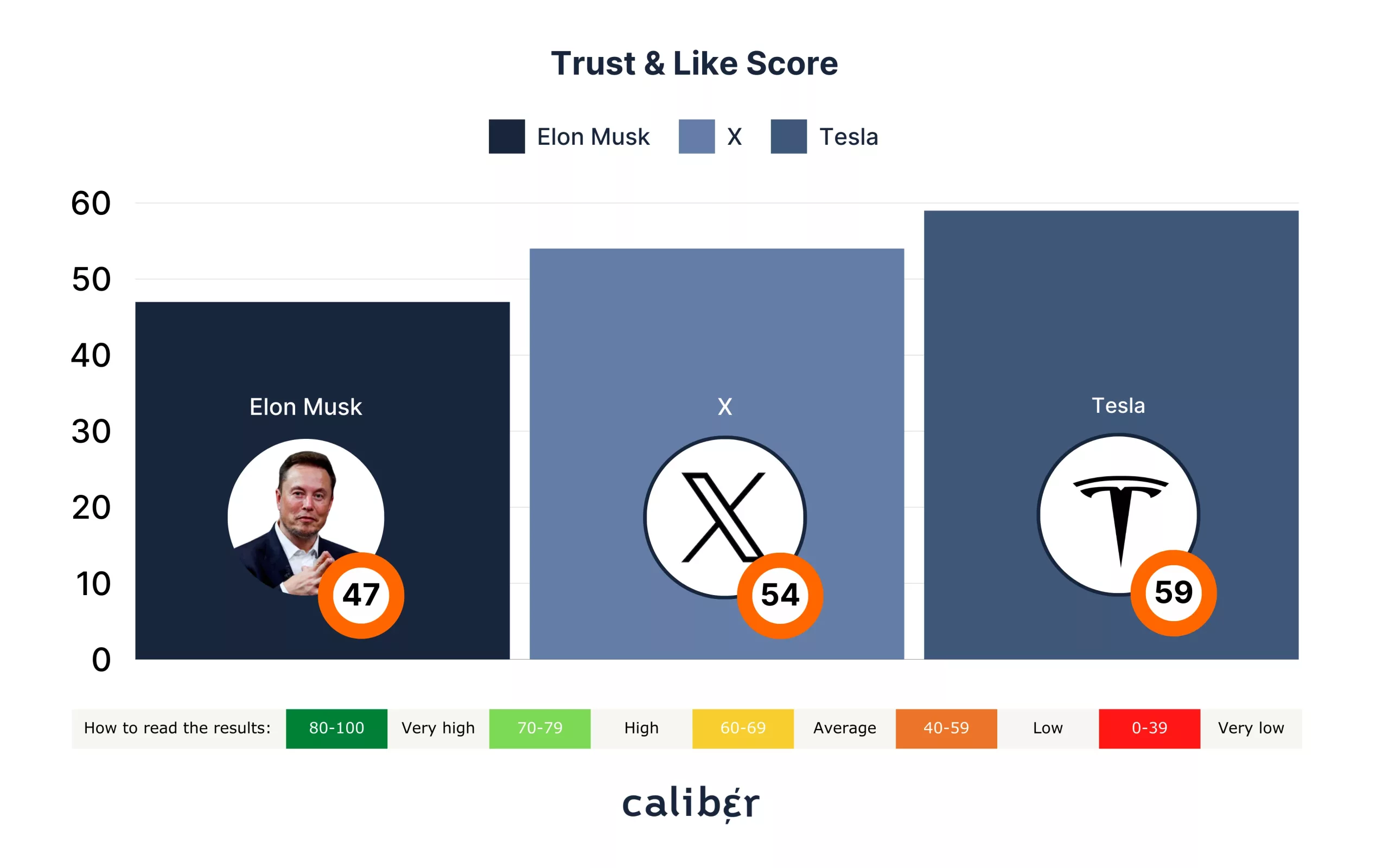

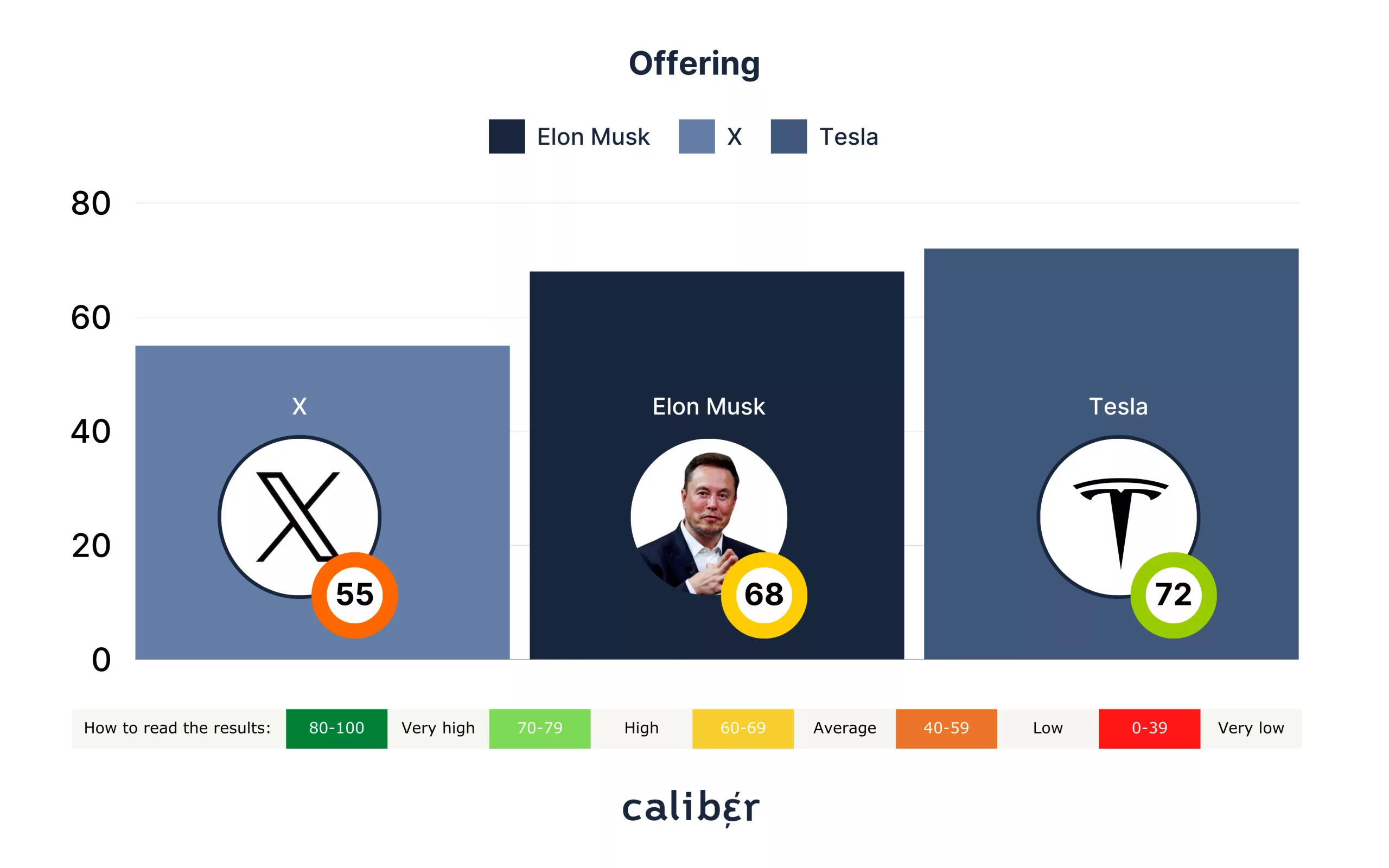

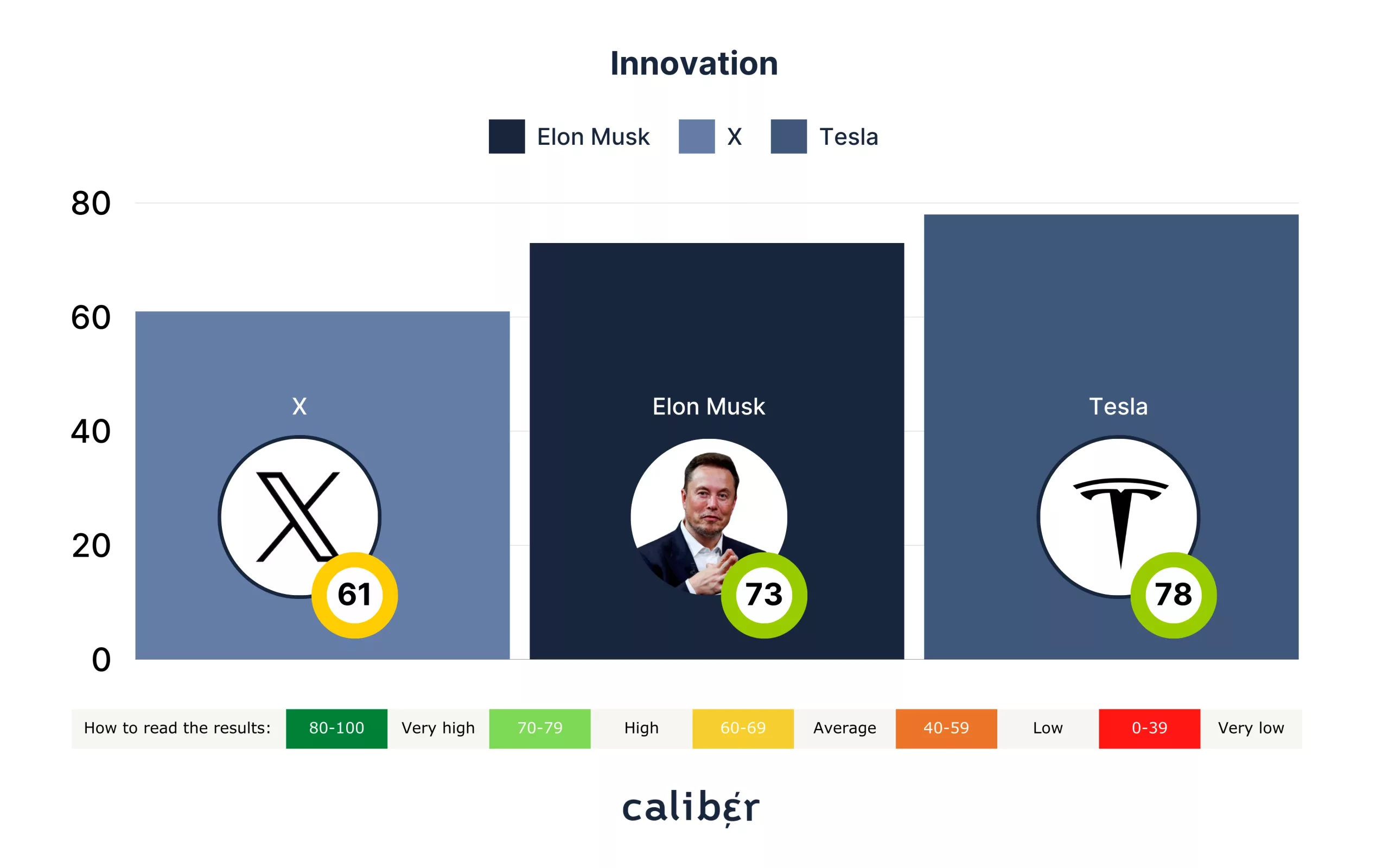

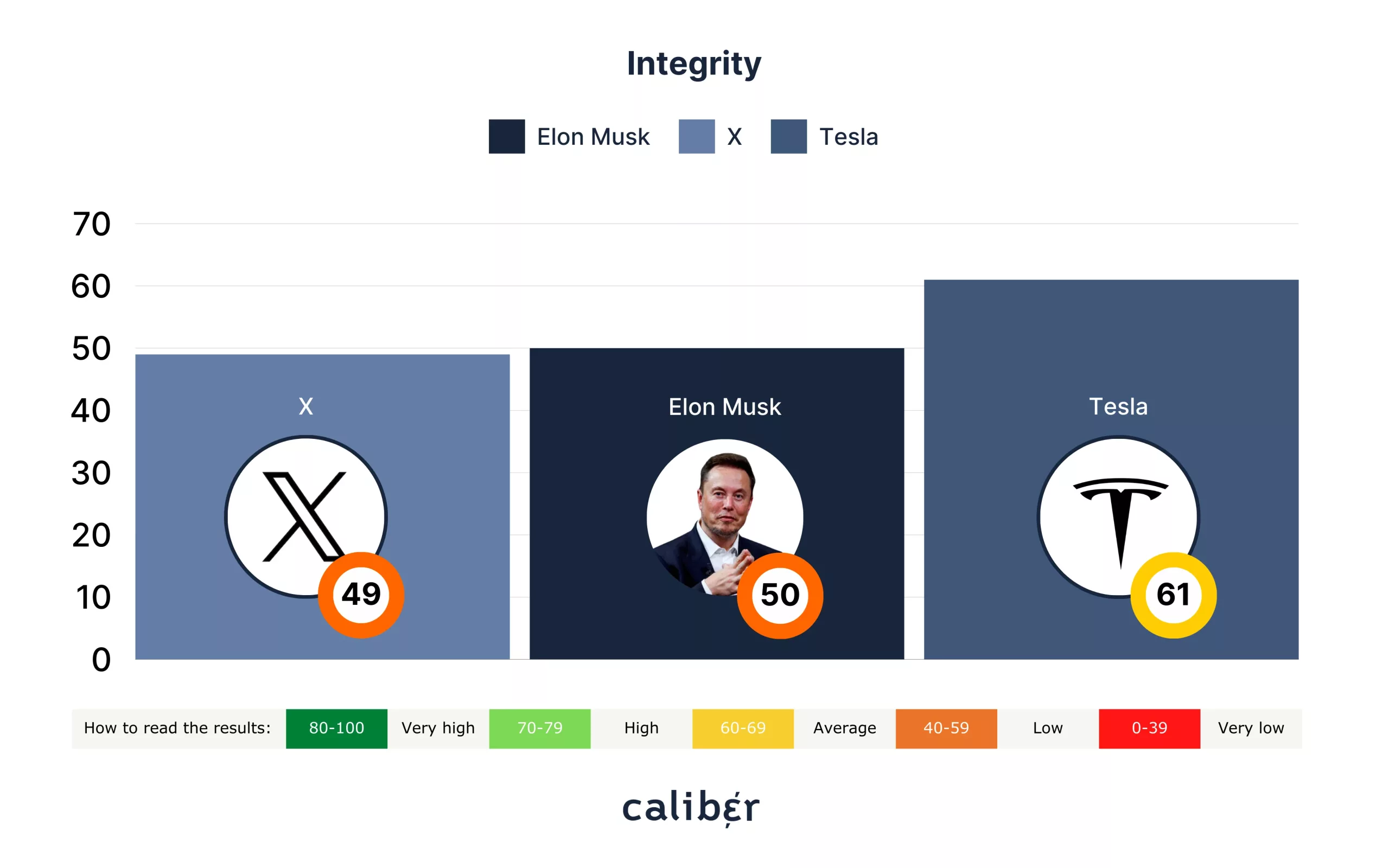

As ever, we recorded a Trust & Like Score for each company, plus a score for the dozen brand and reputation attributes we always measure.**

As the carousel below shows, the scores suggest what’s driving — and dragging down — the reputation of the tech sector, with the companies scoring highest on Innovation, Offering and Inspiration — and lowest on Environment, Relevance and Integrity.

What’s interesting here — and will be especially relevant for what follows — is that Amazon has the best reputation of the 12 companies we considered, appearing in the top three for every attribute.

By contrast, X has the worst reputations, appearing in the bottom three for every attribute.

Having asked respondents to rate each company, we asked them to rate the individuals associated with each one, using almost identical brand and reputation attributes.

The premise was simple: would the individual’s reputation be better or worse than their own company’s — or the same?

In all but two cases, the individual has a worse reputation — though in many instances, the sample size wasn’t quite big enough to ensure statistical significance.

That in and of itself is a telling detail about the apparent “invisibility” of many of these tech titans in the US.

Unsurprisingly, though, we got a statistically significant number of responses about three high-profile executives — Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos.

Broadly speaking, all three have average individual “brands and reputations”. But as we’ve seen, whereas X and Meta have relatively poor corporate reputations, Amazon doesn’t.

Let’s start with Elon Musk. The Tesla CEO and owner of X has a worse Trust & Like Score than both companies — though their reputations aren’t especially strong either.

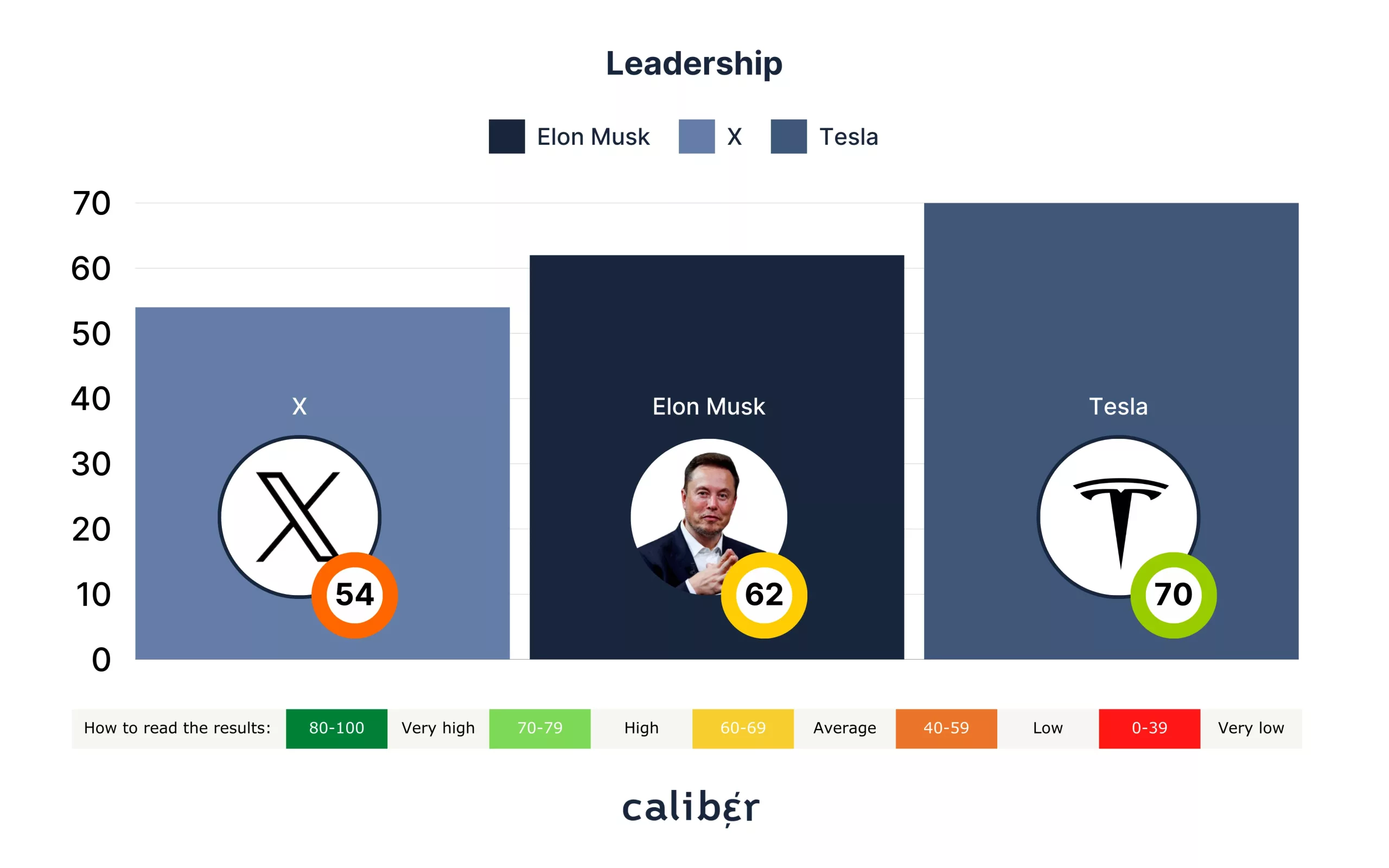

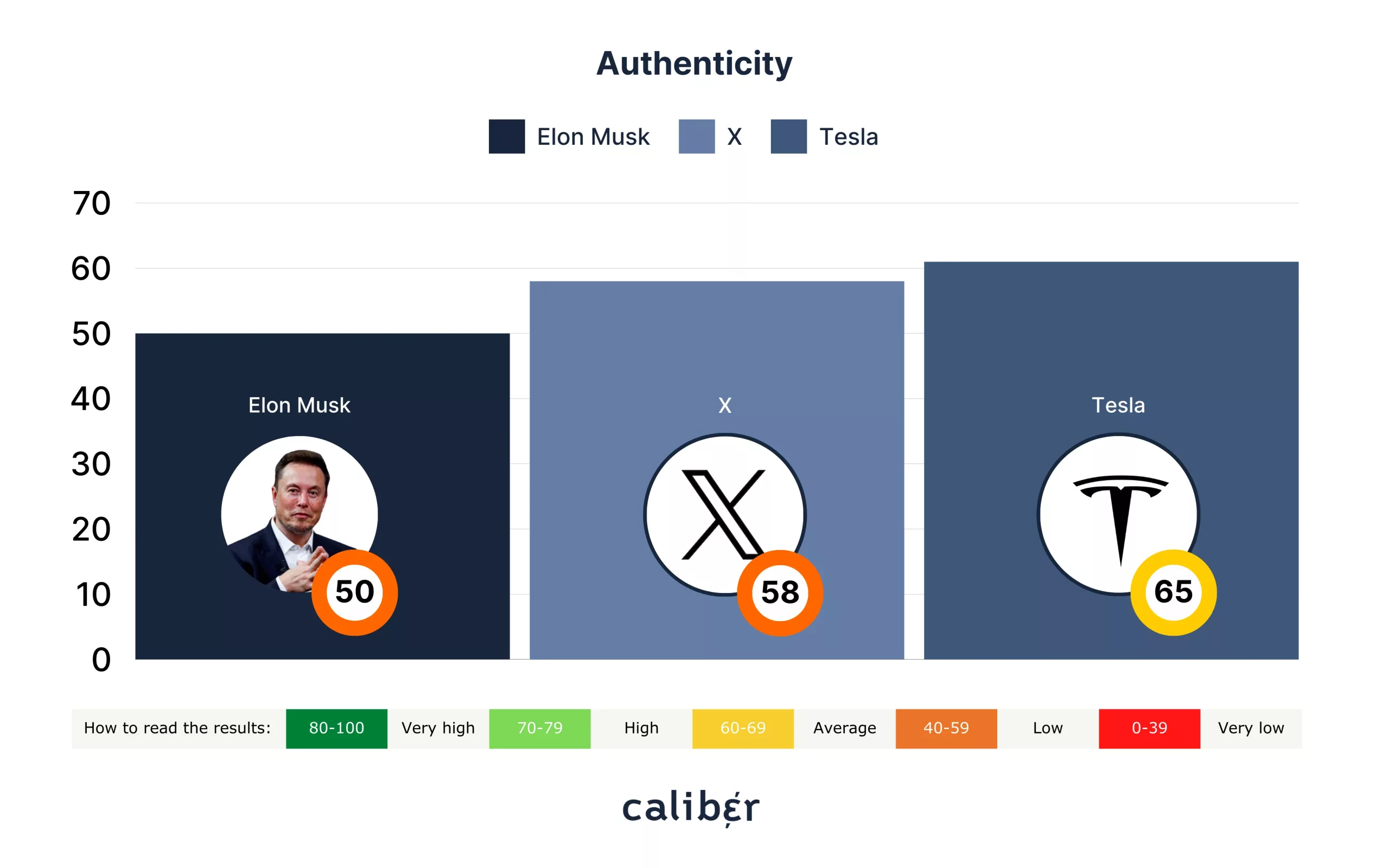

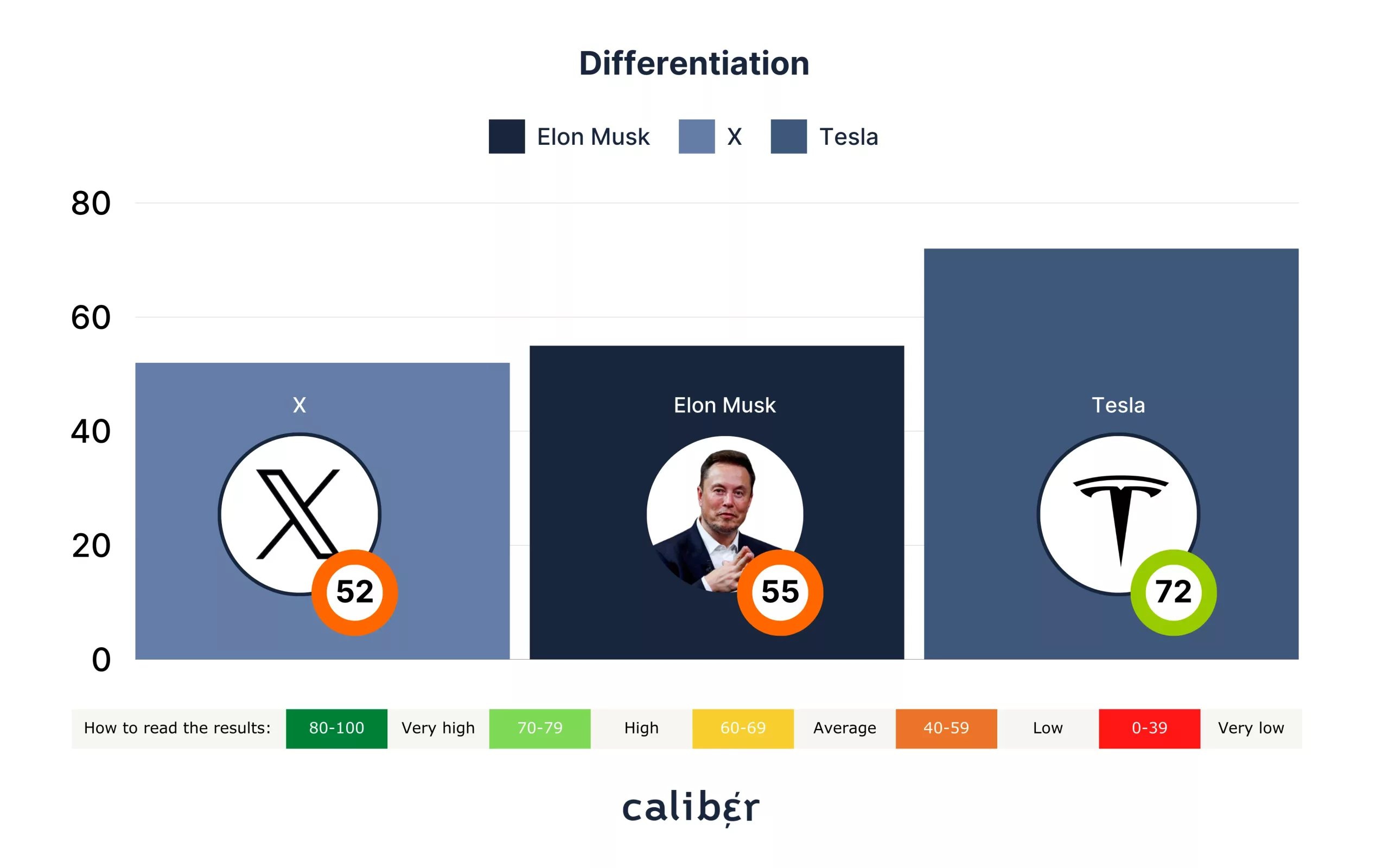

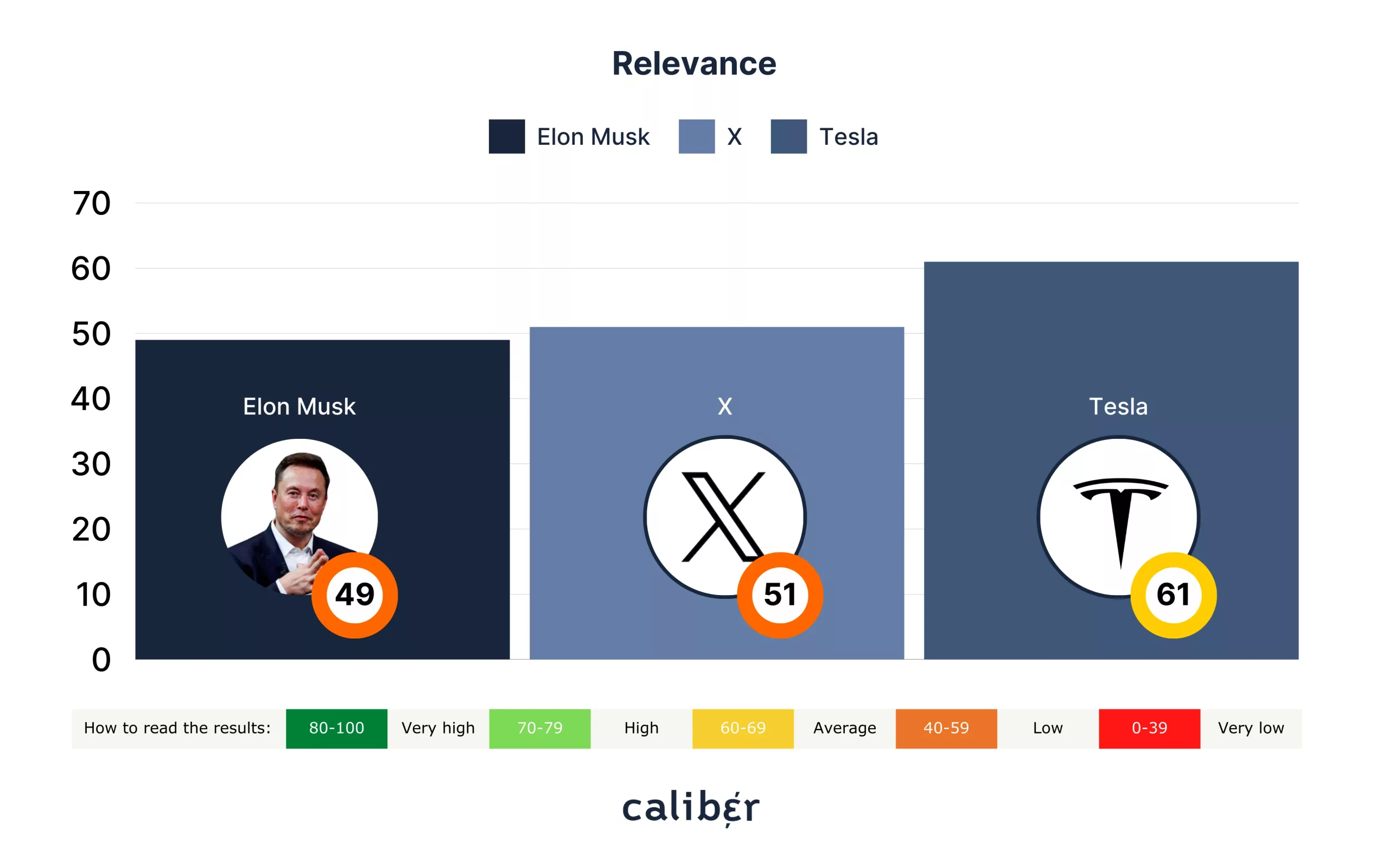

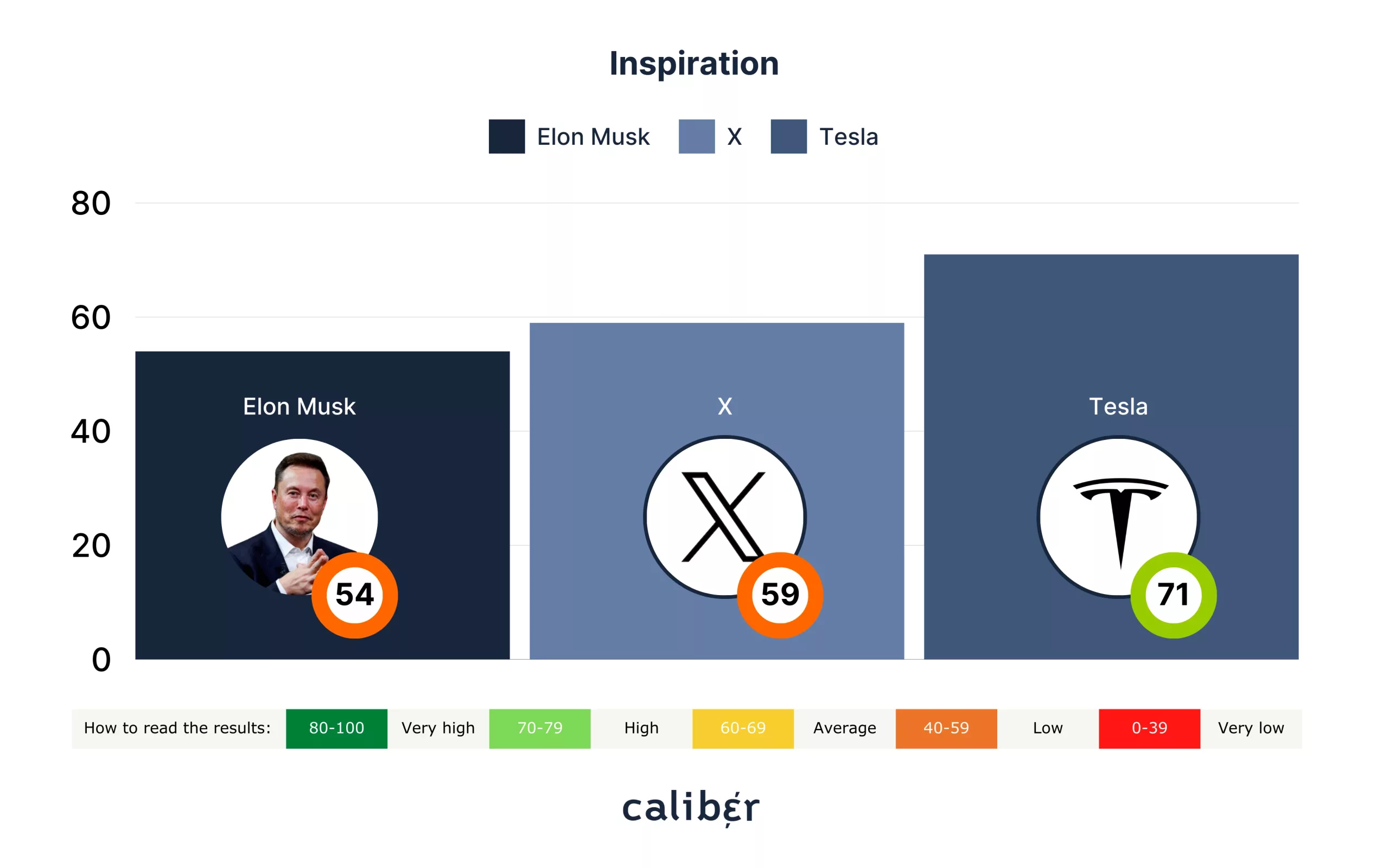

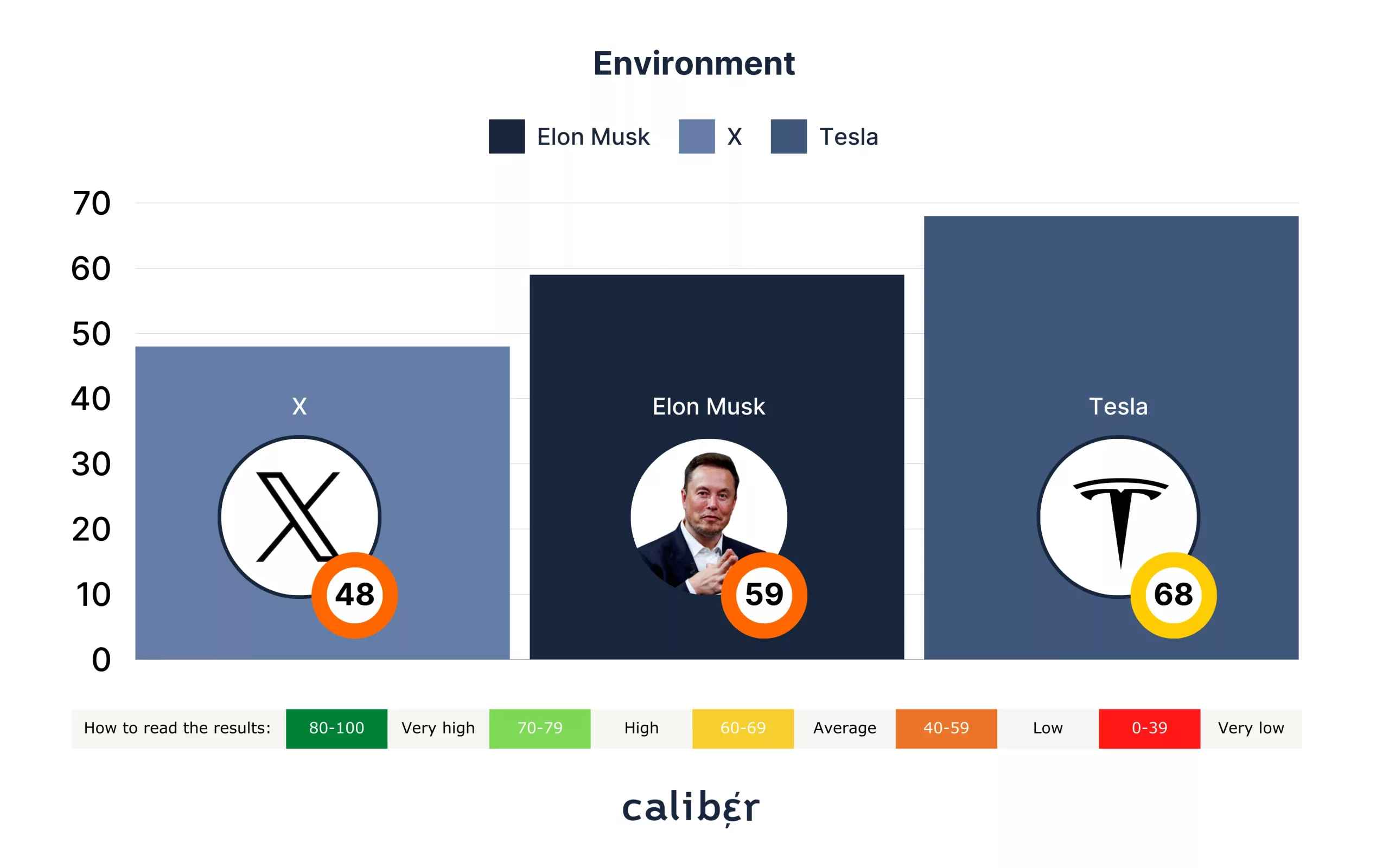

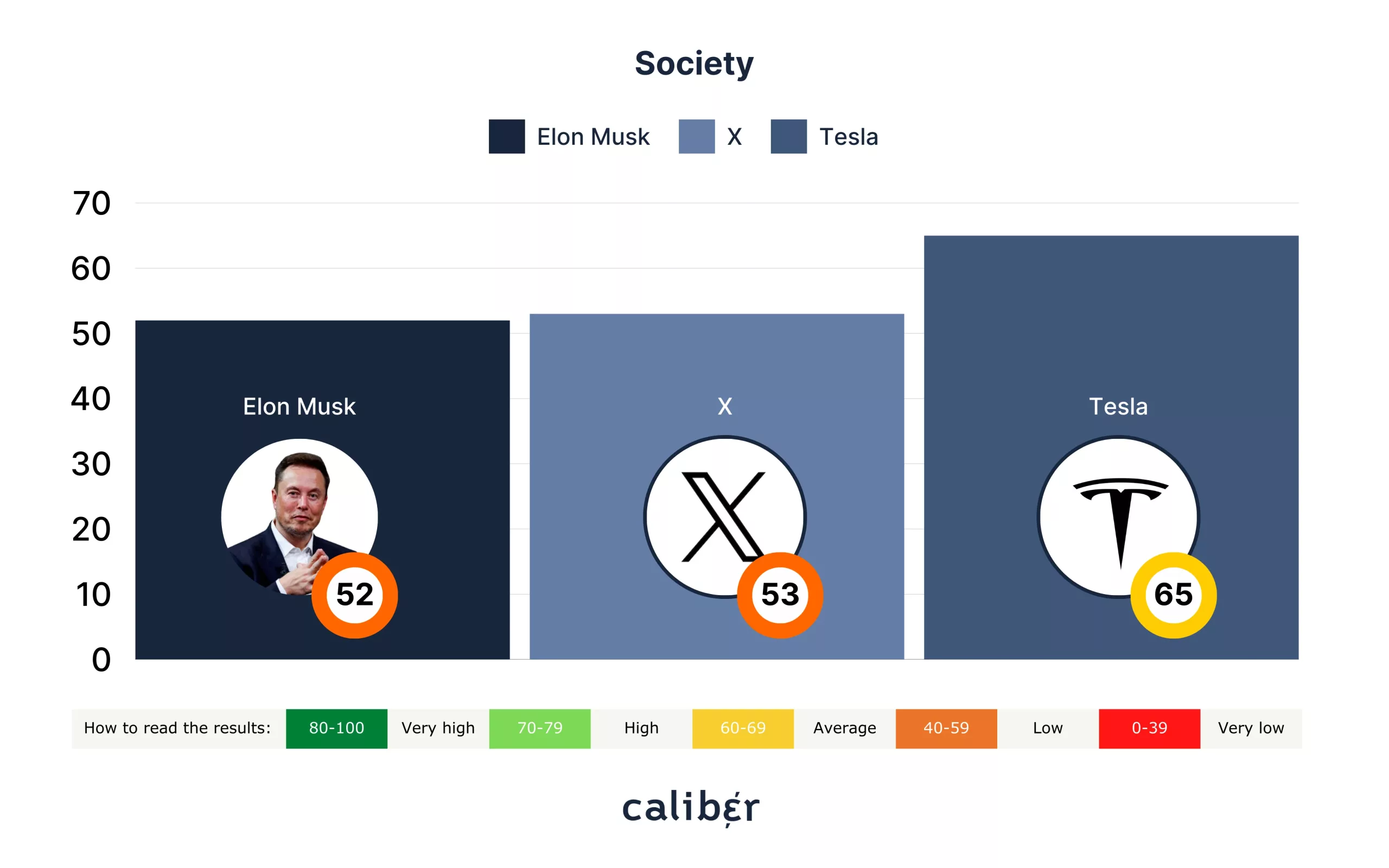

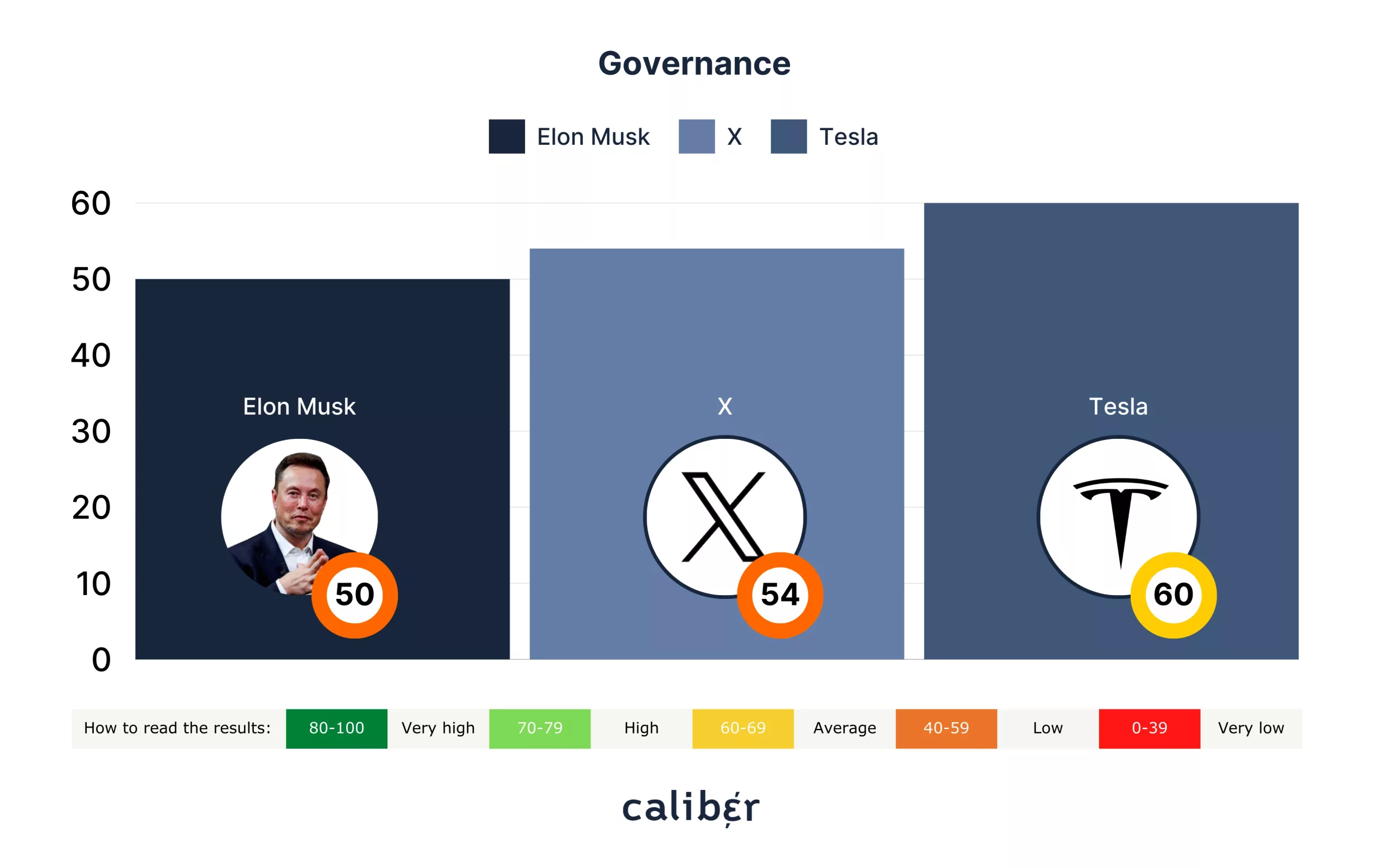

As the carousel below shows, his brand and reputation scores are closer to X’s across seven attributes (Integrity, Authenticity, Differentiation, Relevance, Inspiration, Society, and Governance).

Musk’s scores are much closer to Tesla’s for Offering, Innovation and Environment, while for Leadership his personal score sits right between X’s and Tesla’s.

Finally, the data reveals an interesting — but perhaps not altogether surprising — gender divide.

Musk gets much higher scores among men than women across every brand and reputation attribute, including a starkly different Trust & Like Score. We include three of them below:

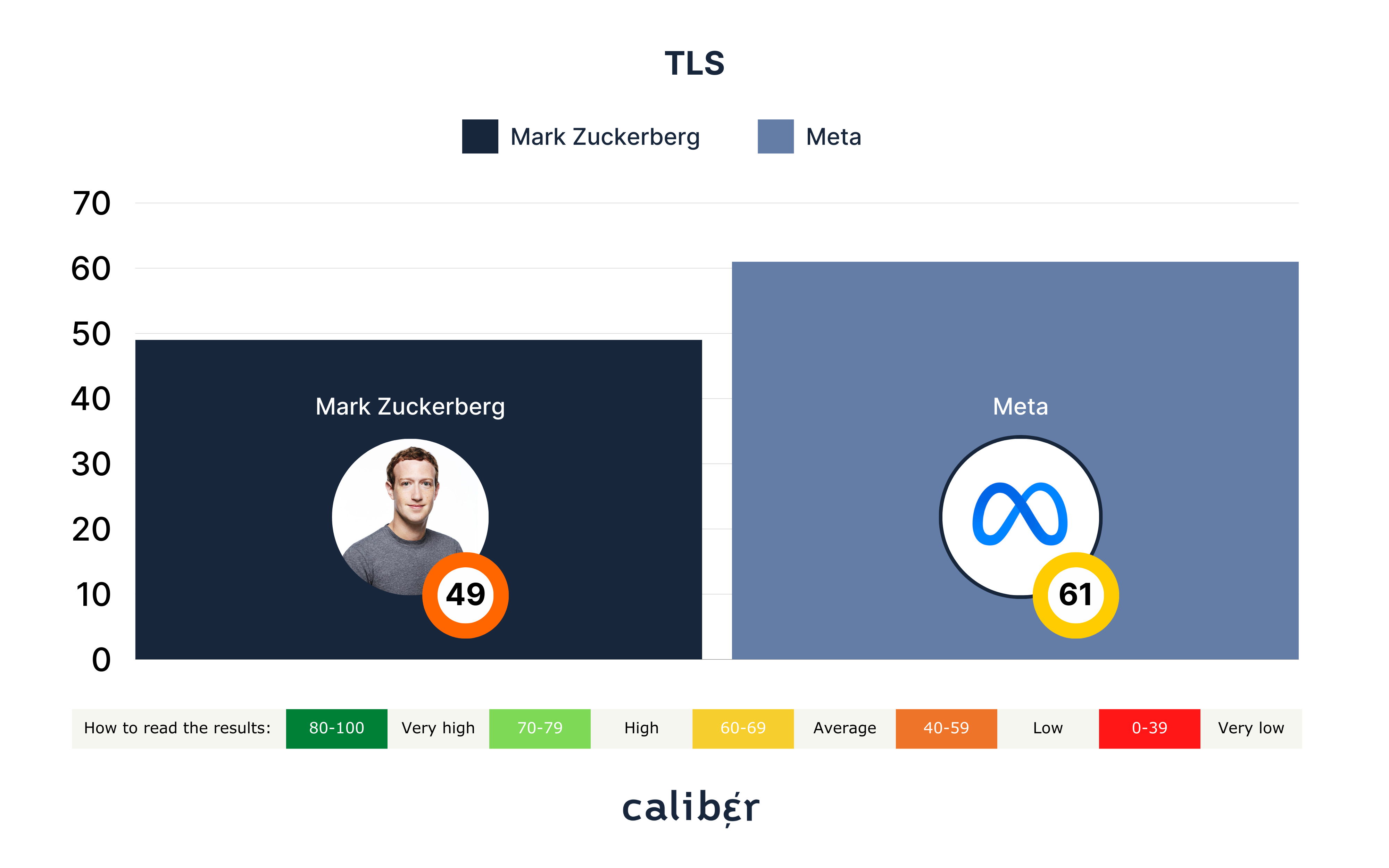

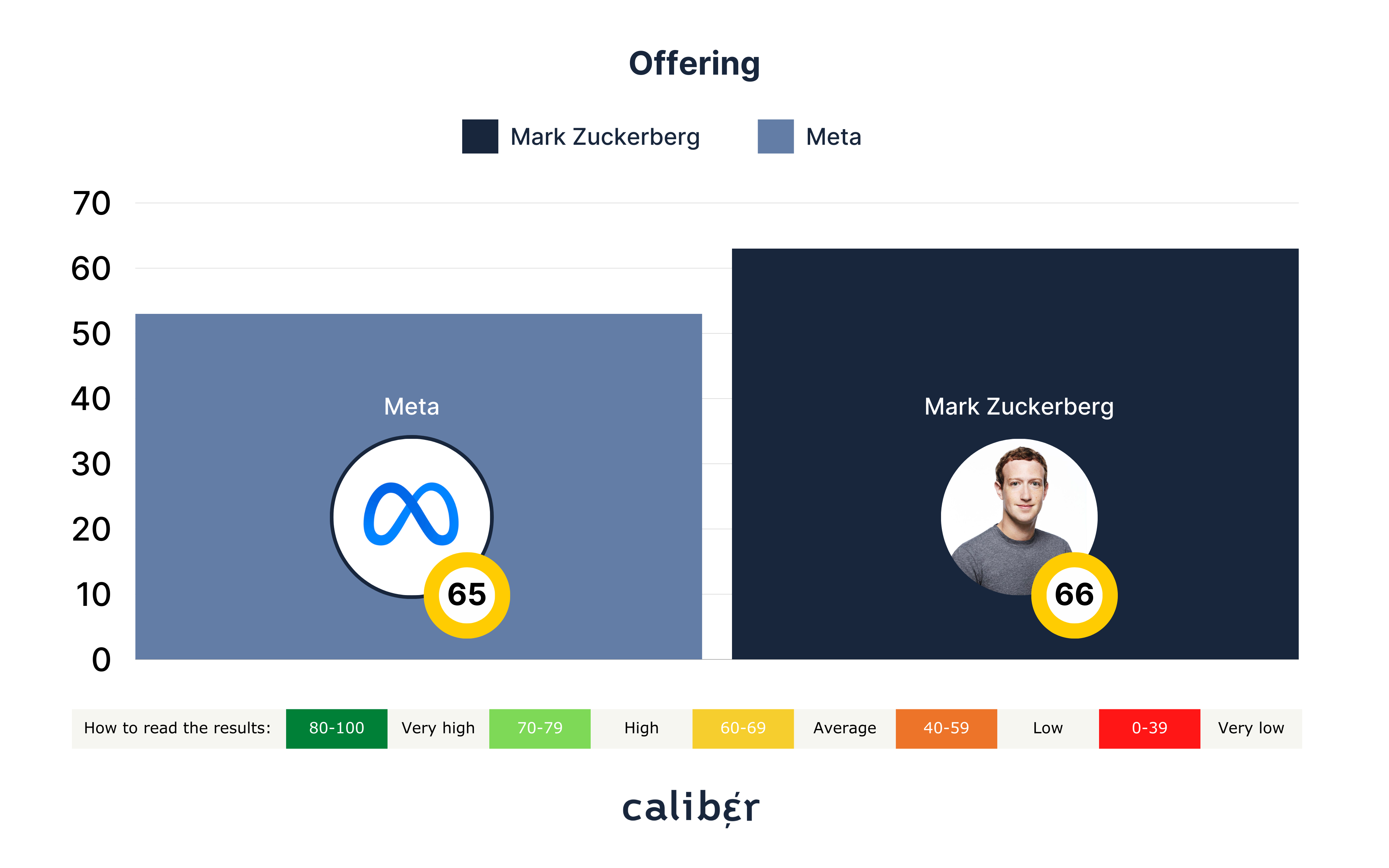

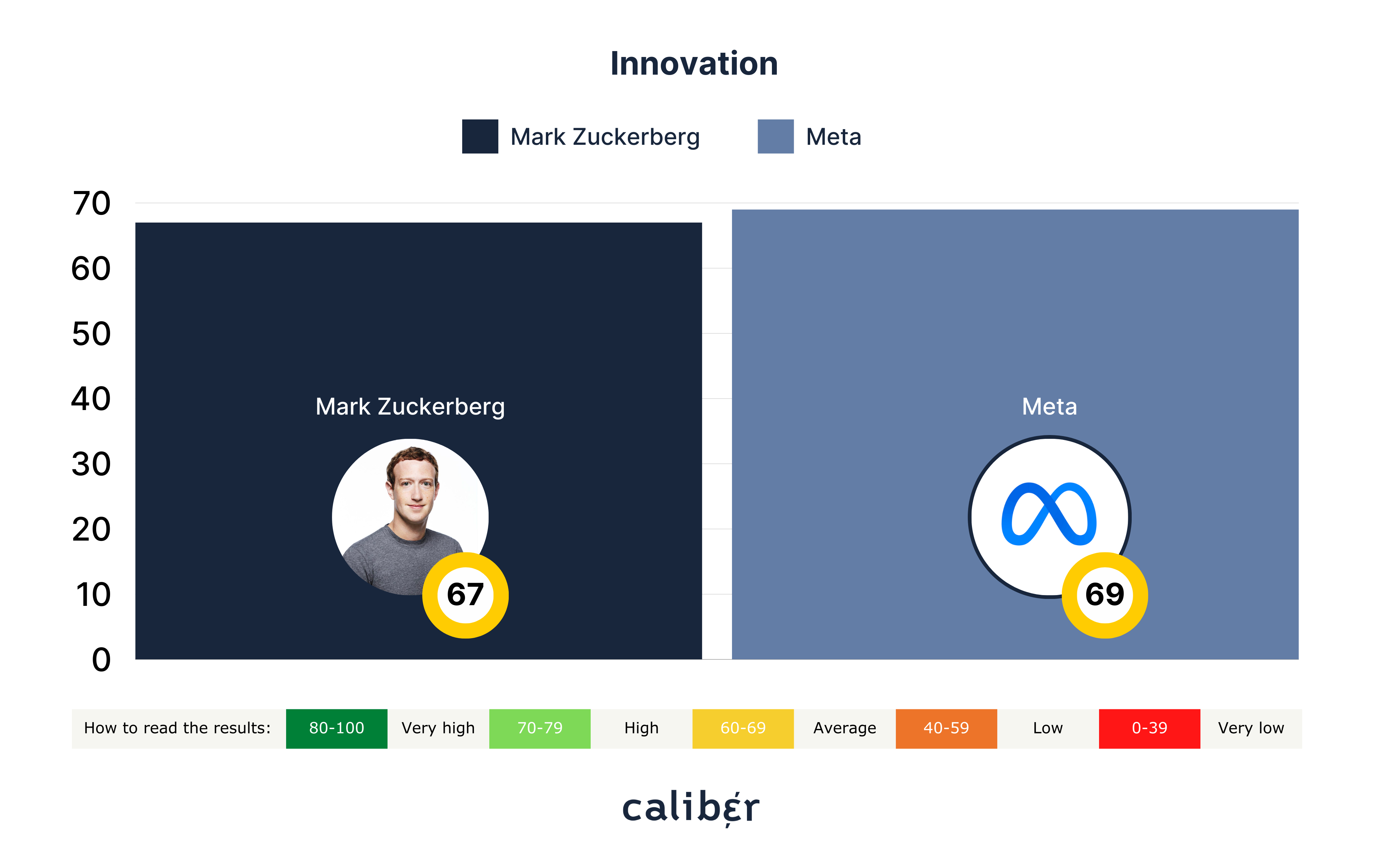

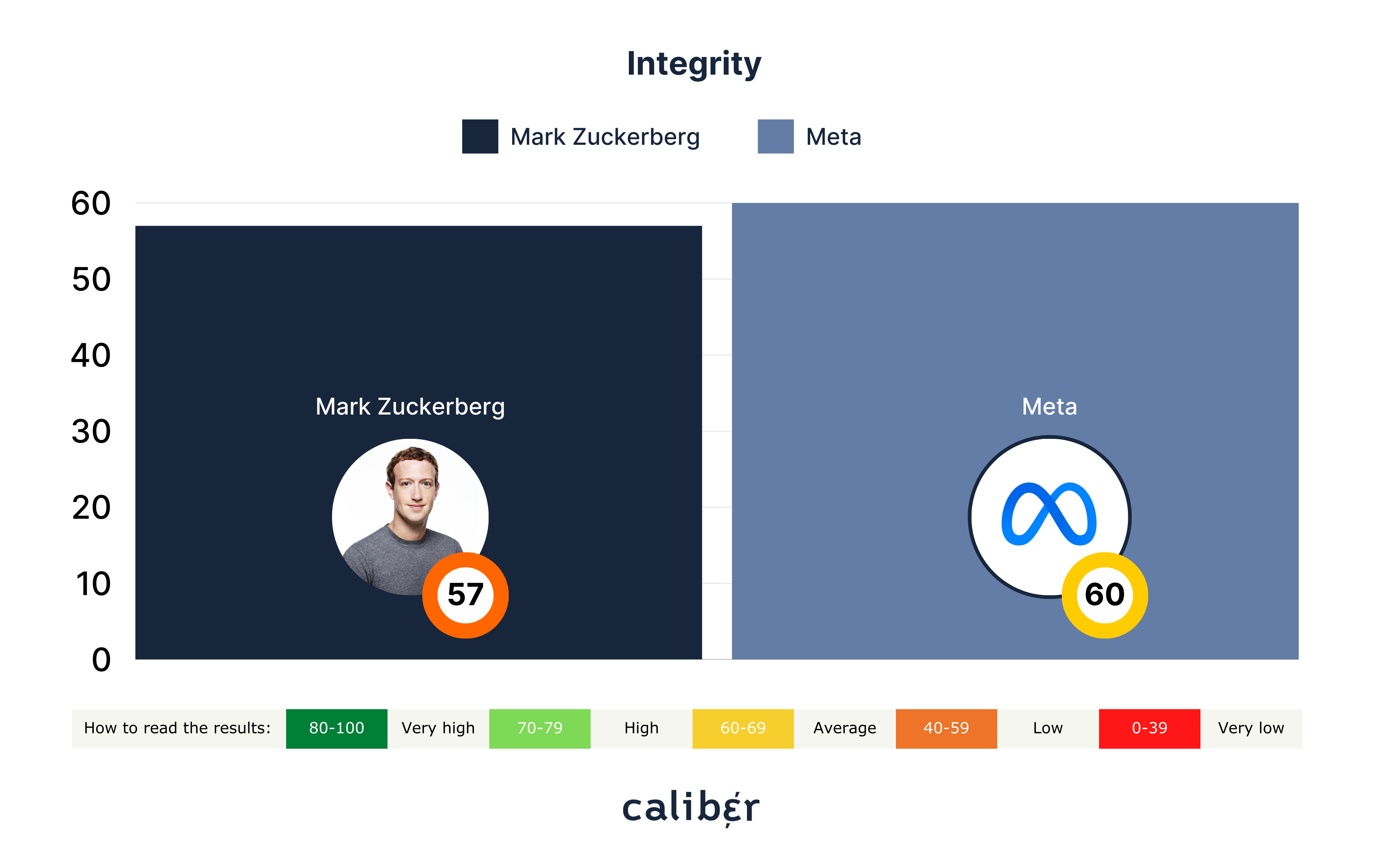

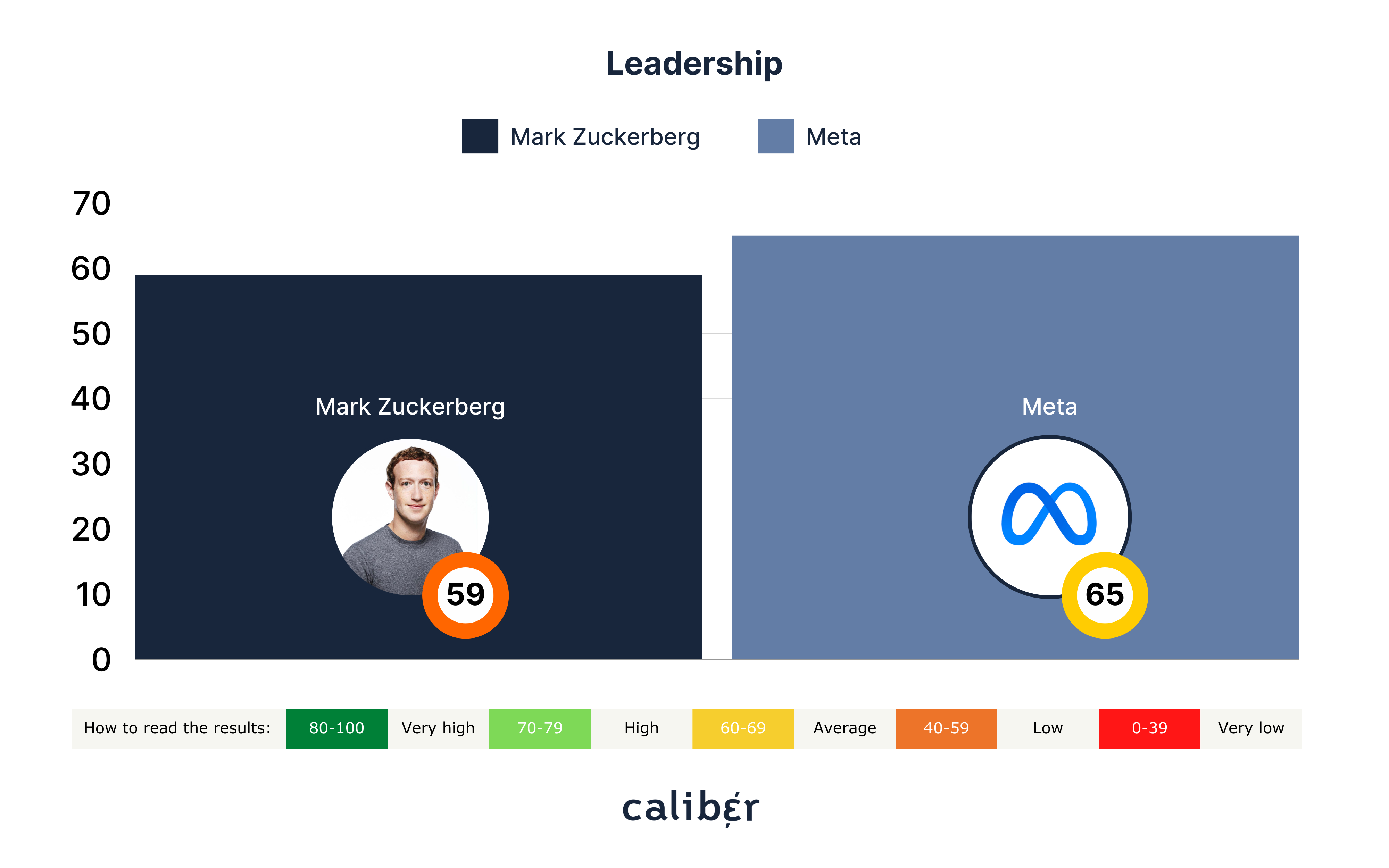

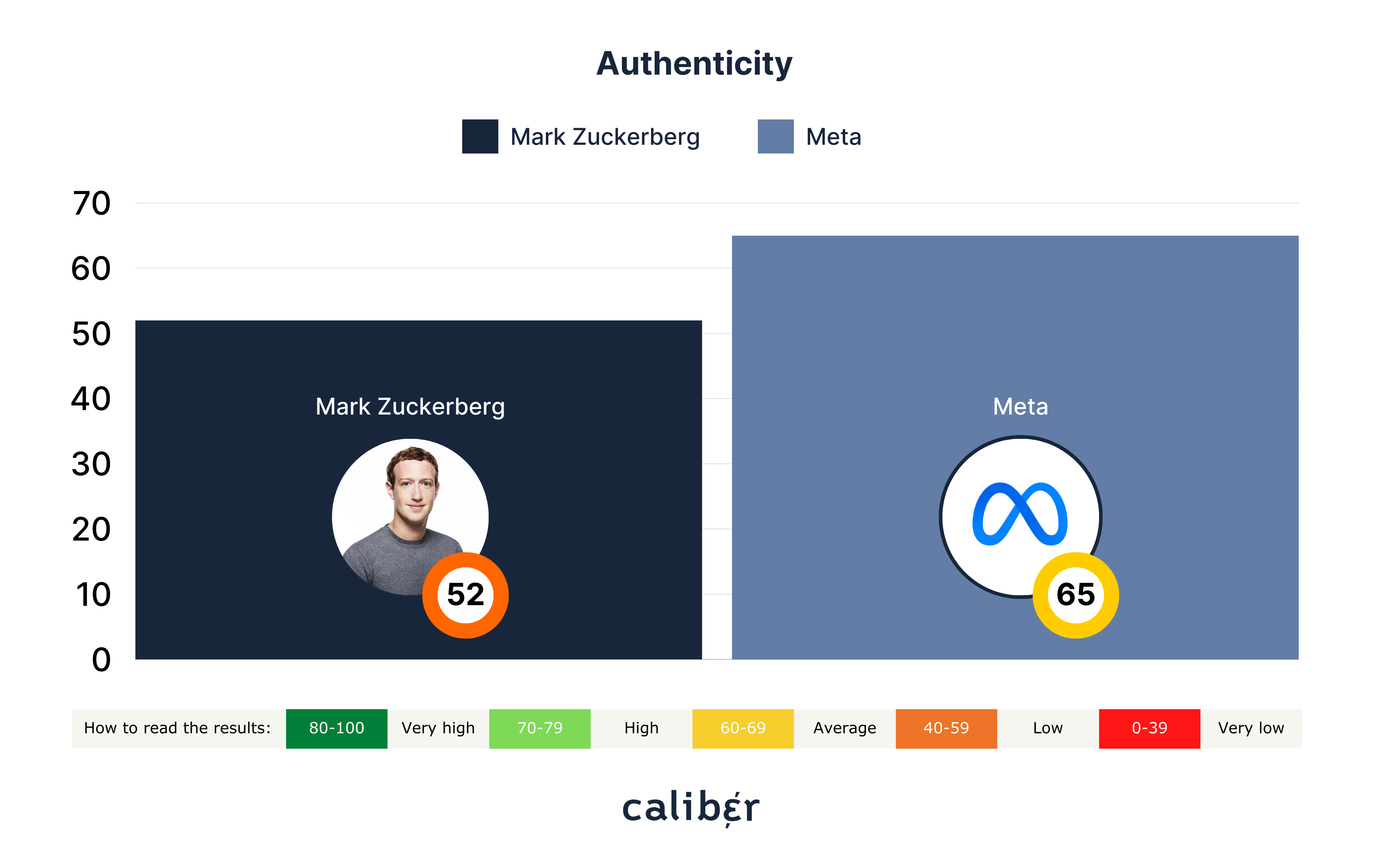

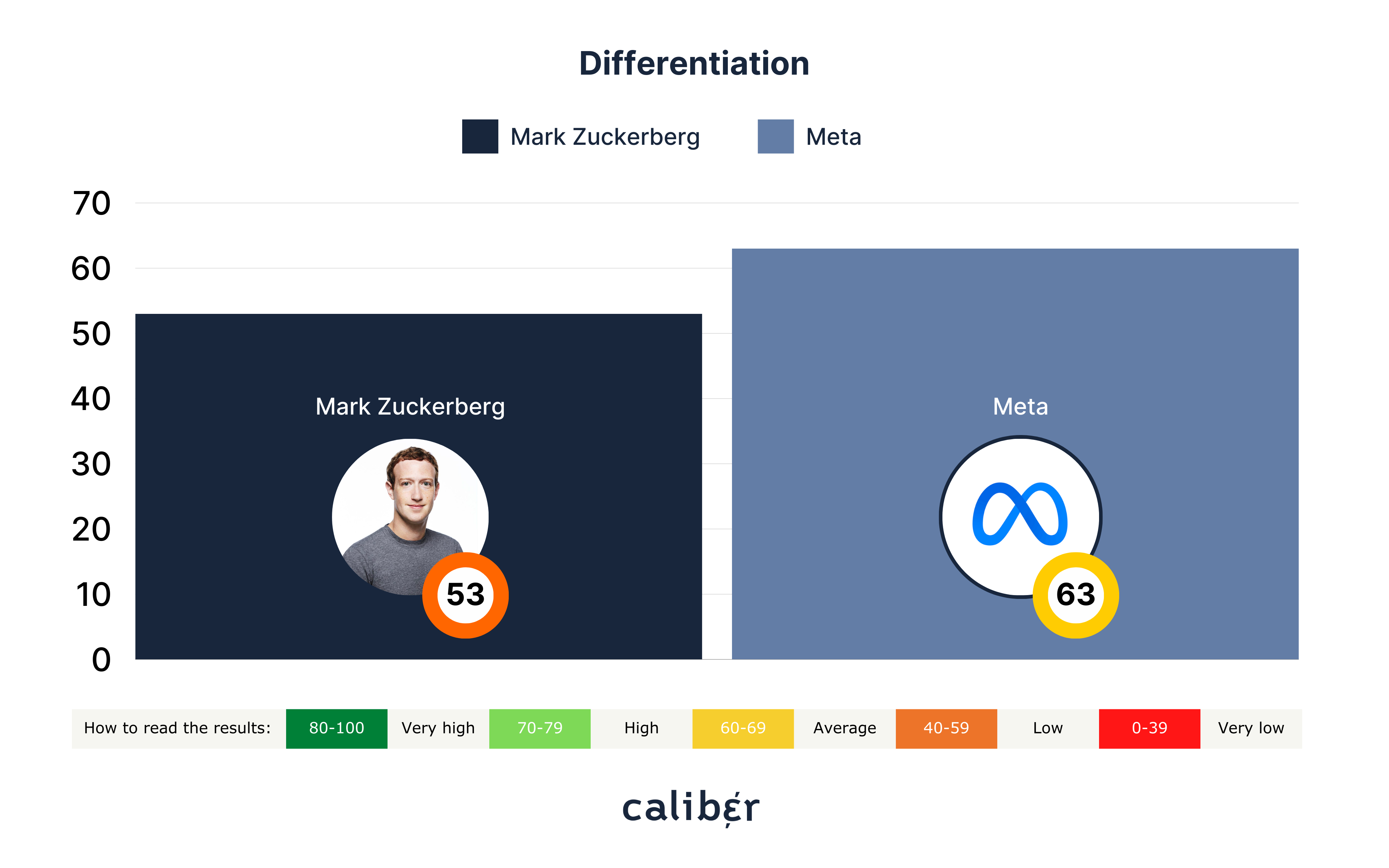

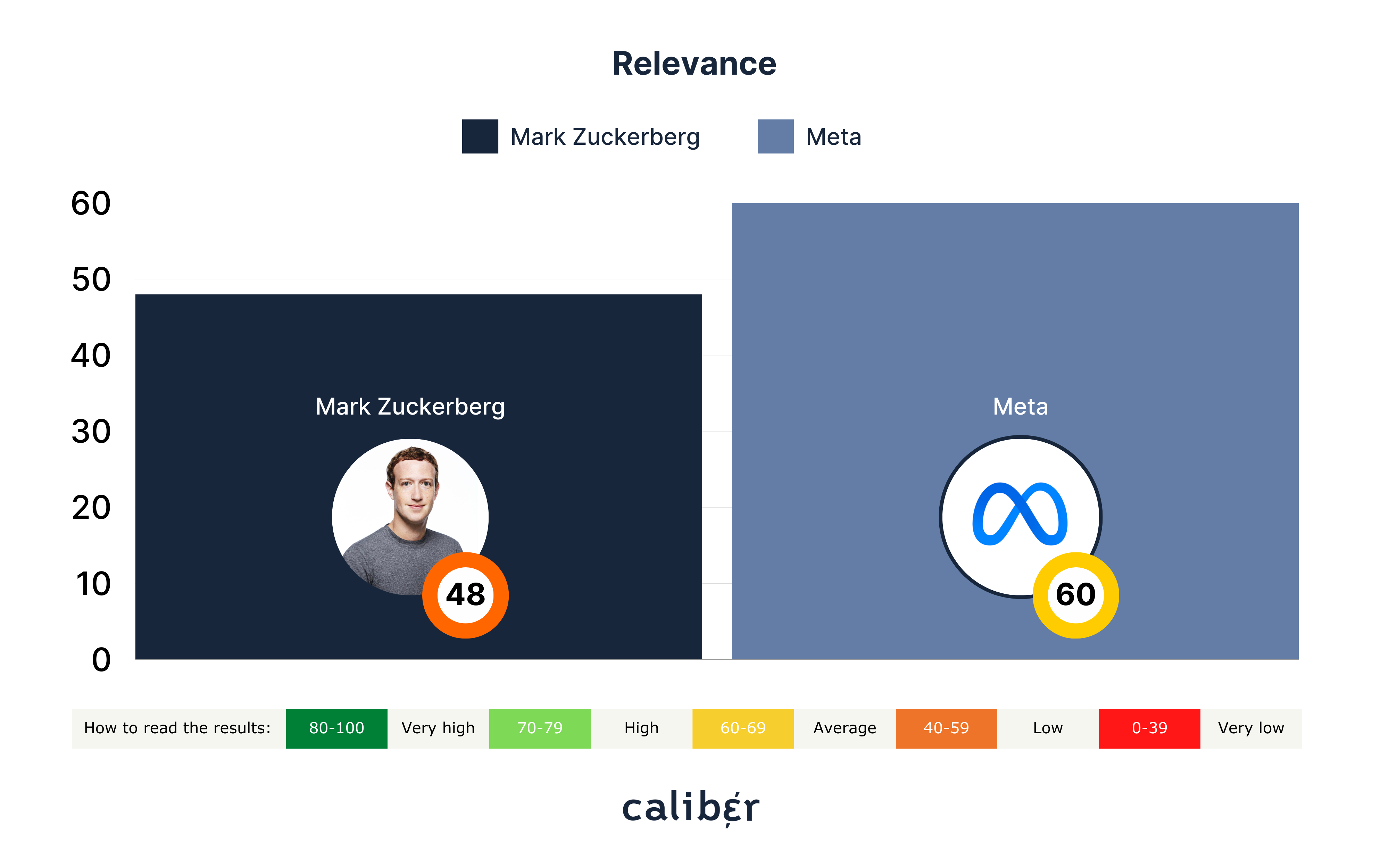

Next, we turn to Mark Zuckerberg, who has a worse Trust & Like Score than Meta, the social media giant he founded.

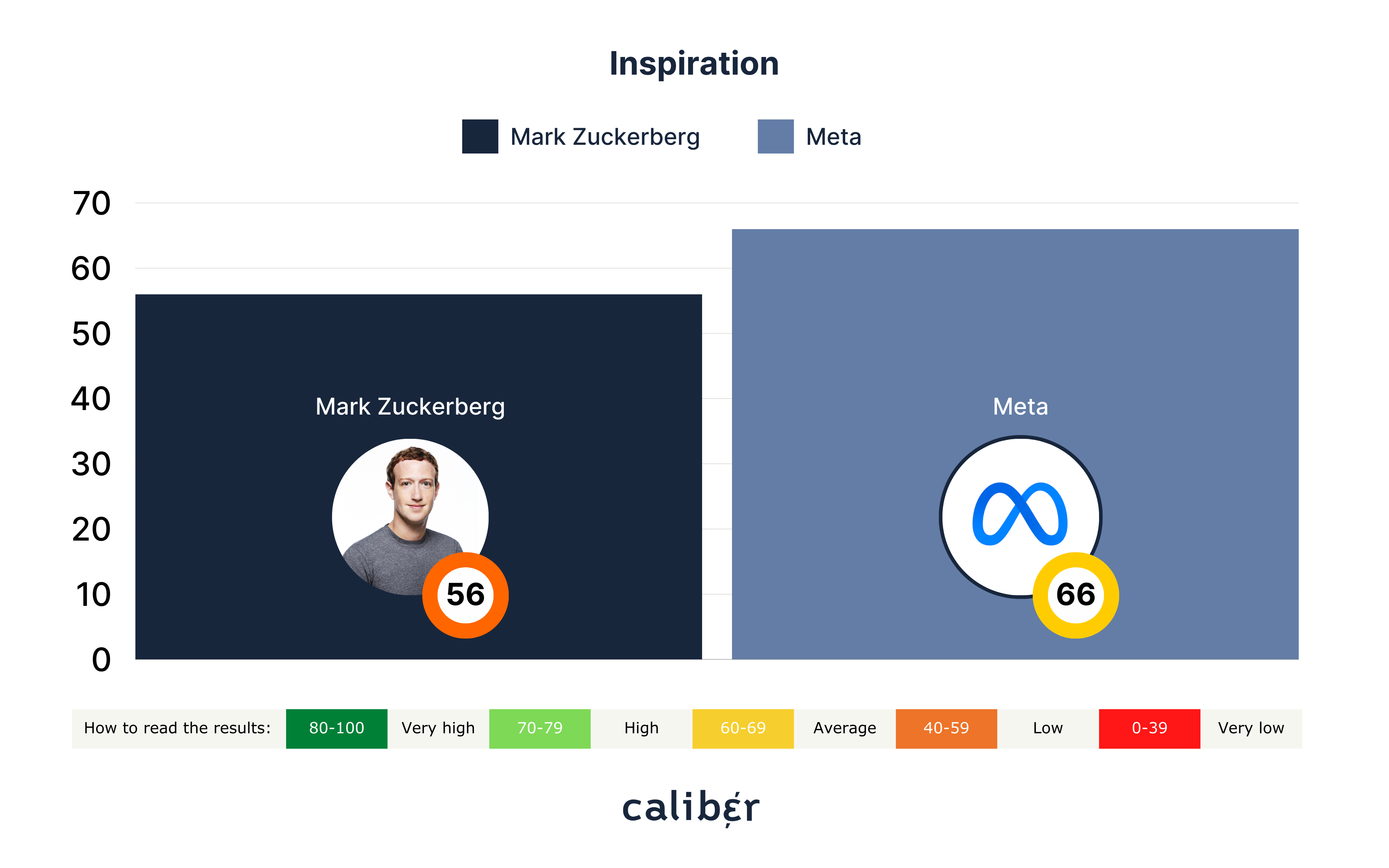

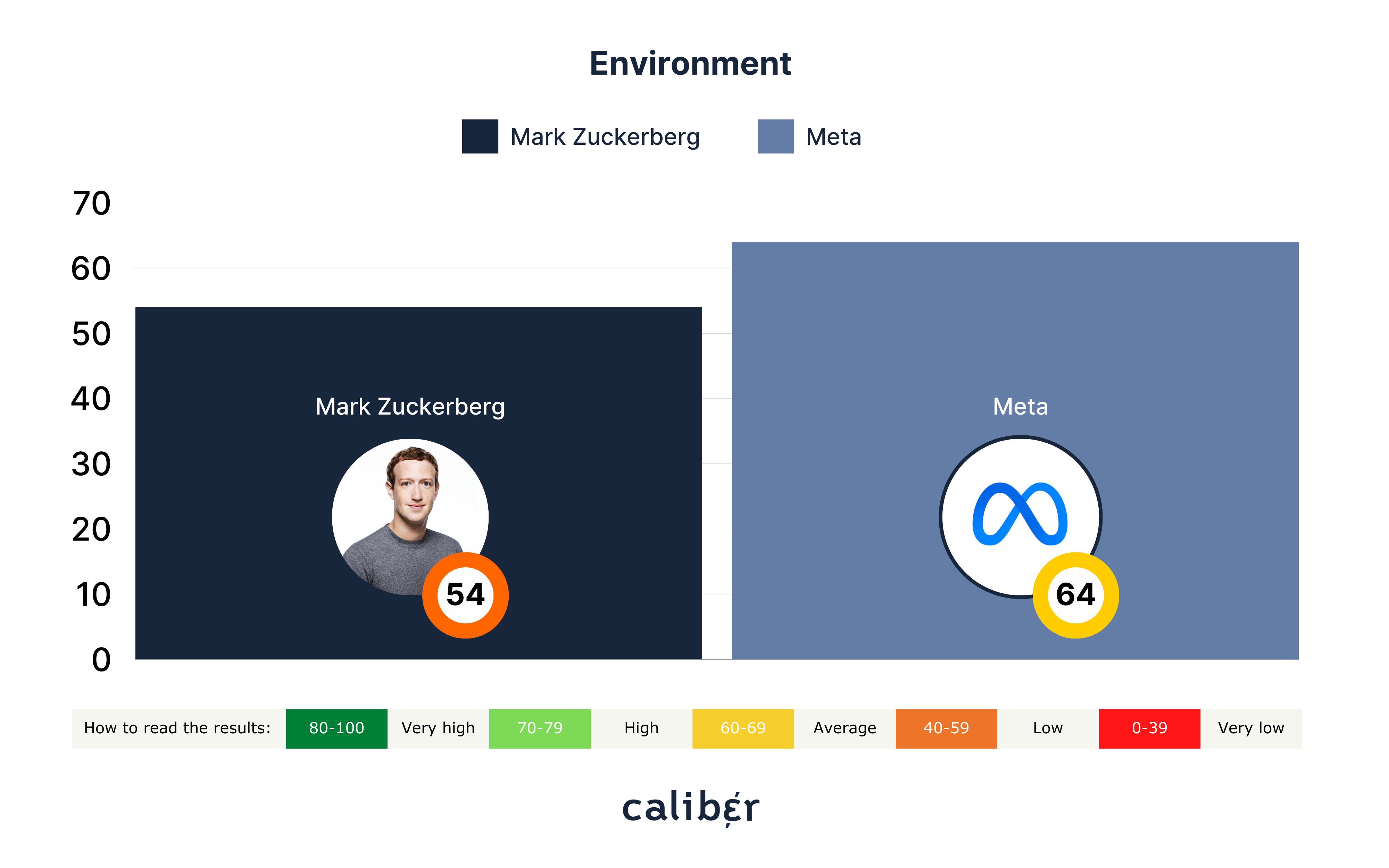

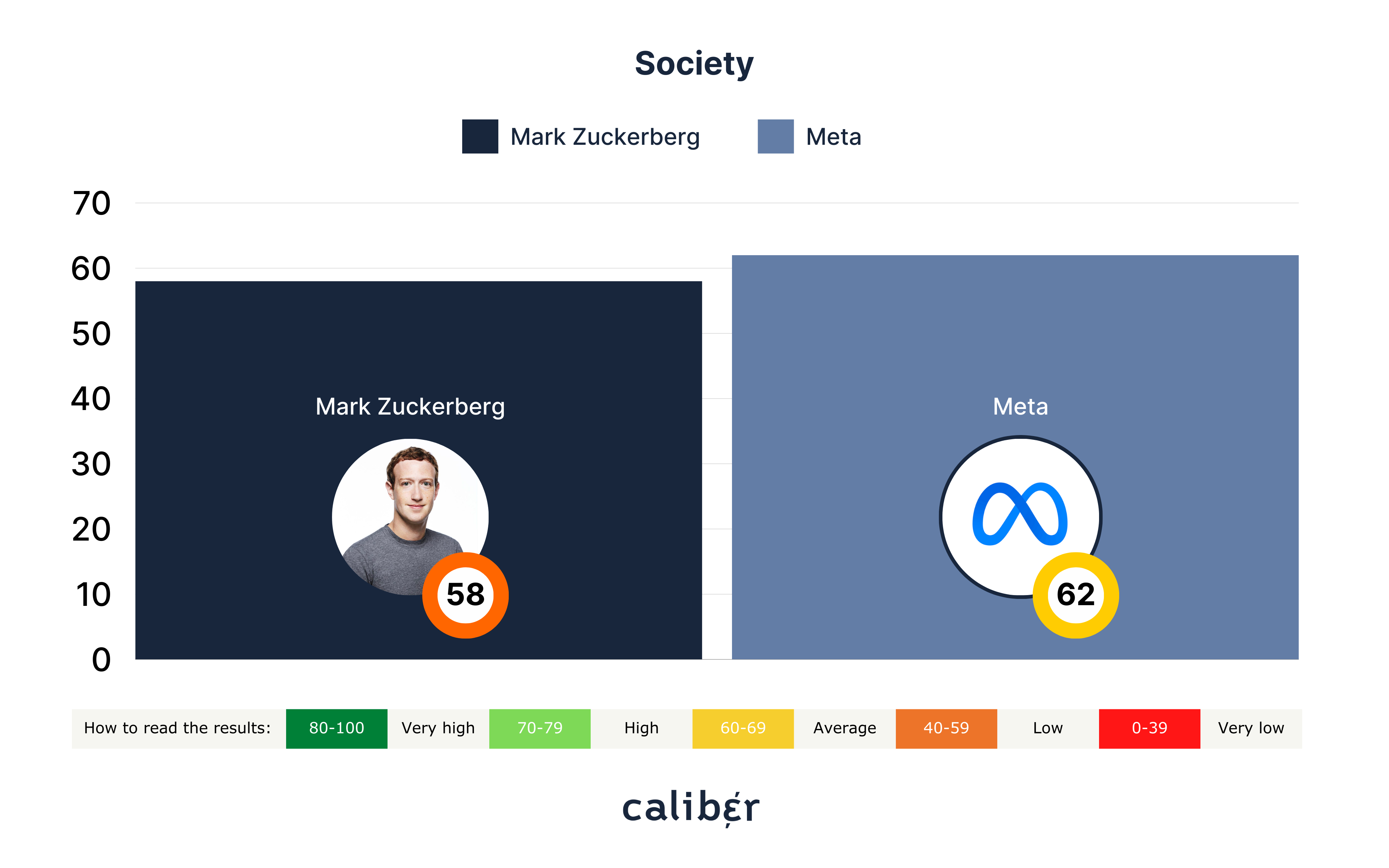

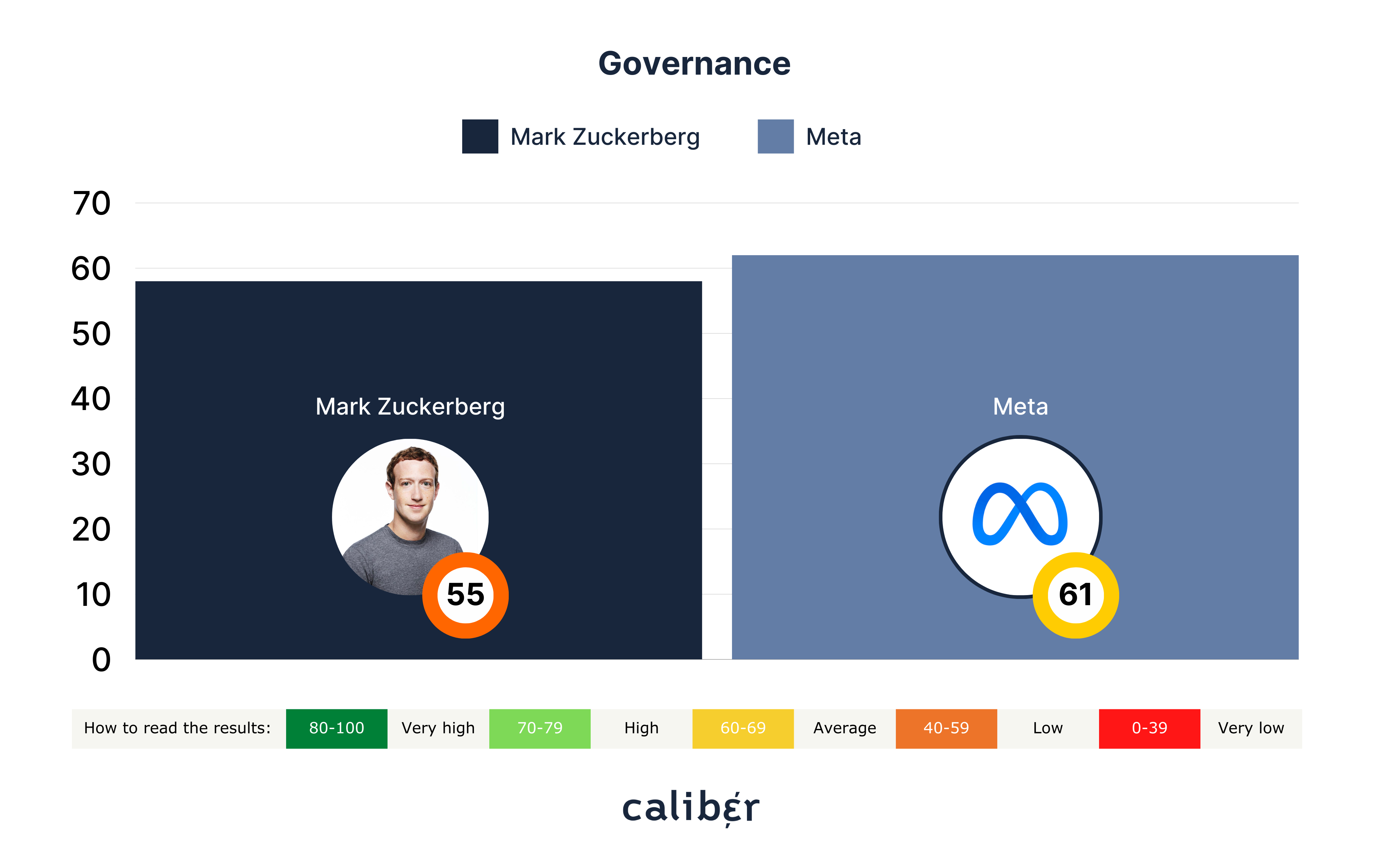

In fact, as the carousel below shows, his brand and reputation scores are lower than Meta’s across every attribute but one: Offering.

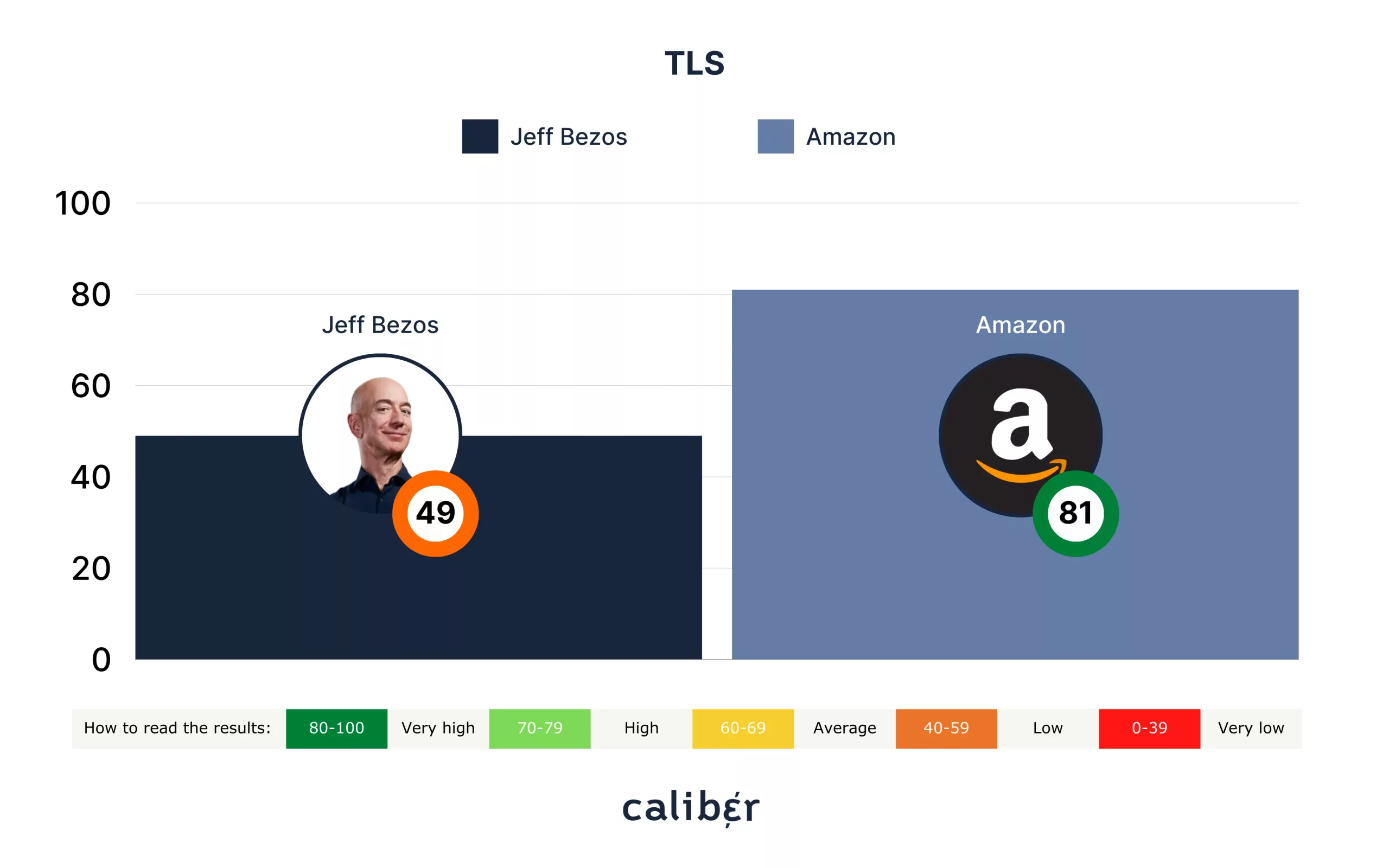

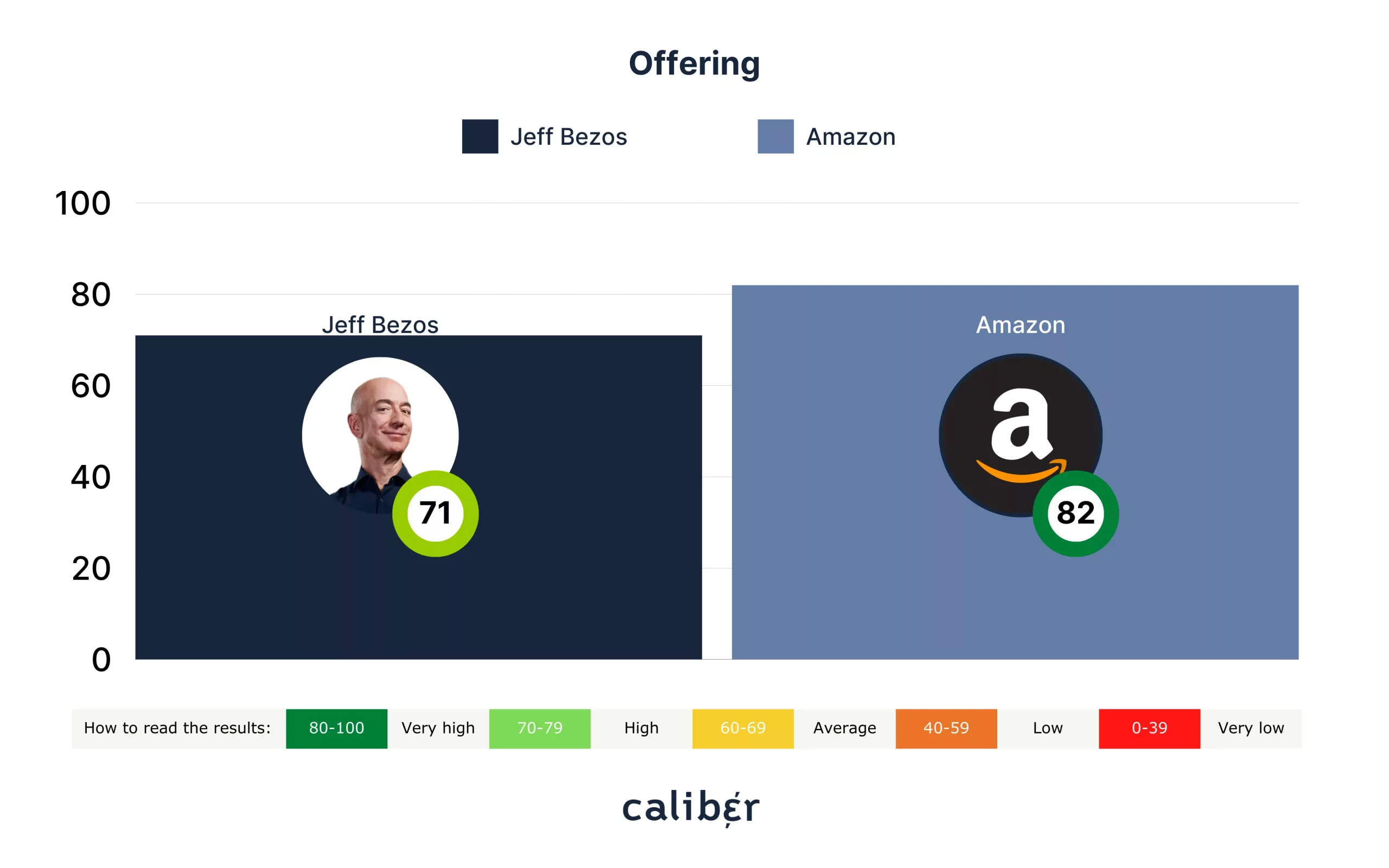

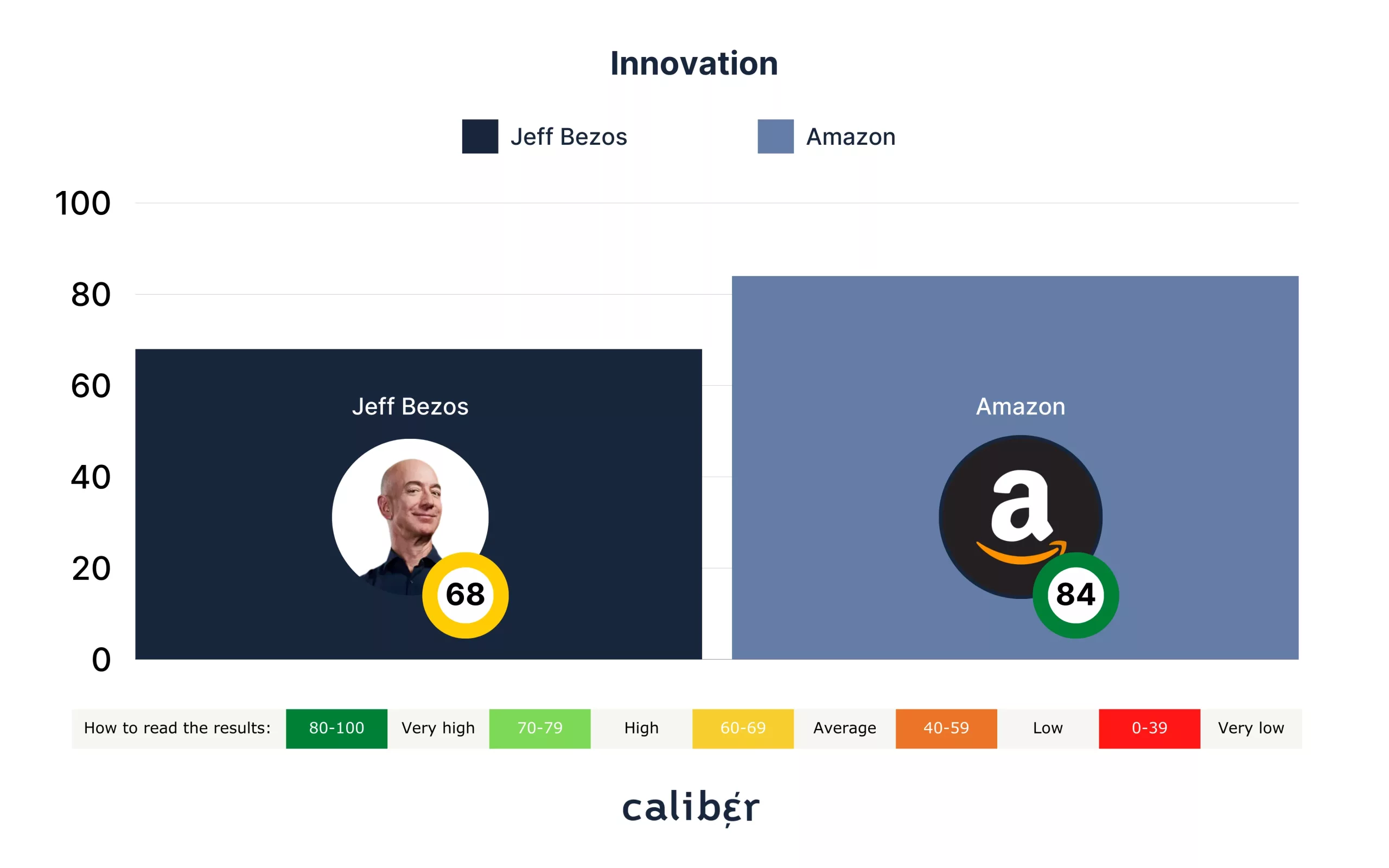

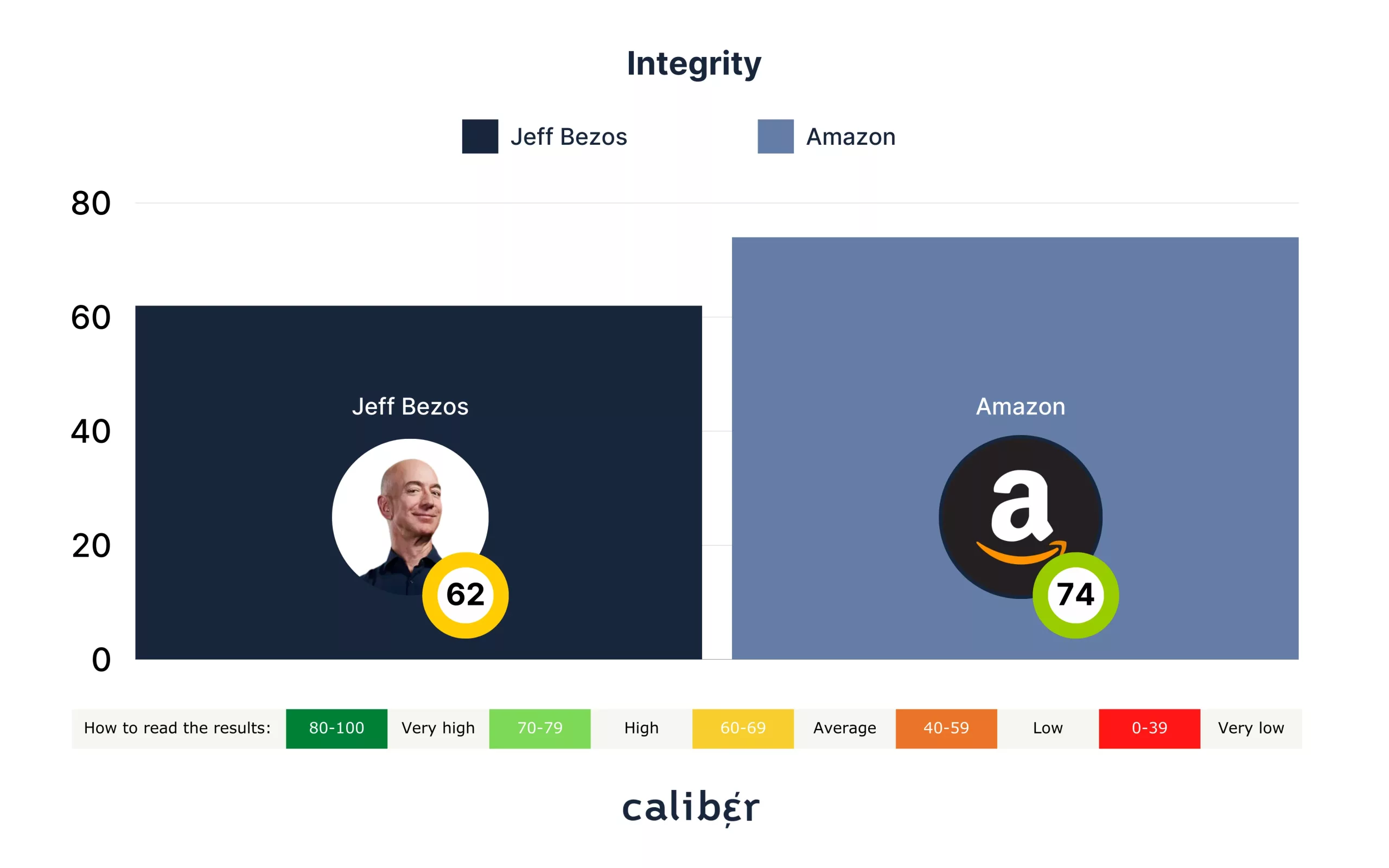

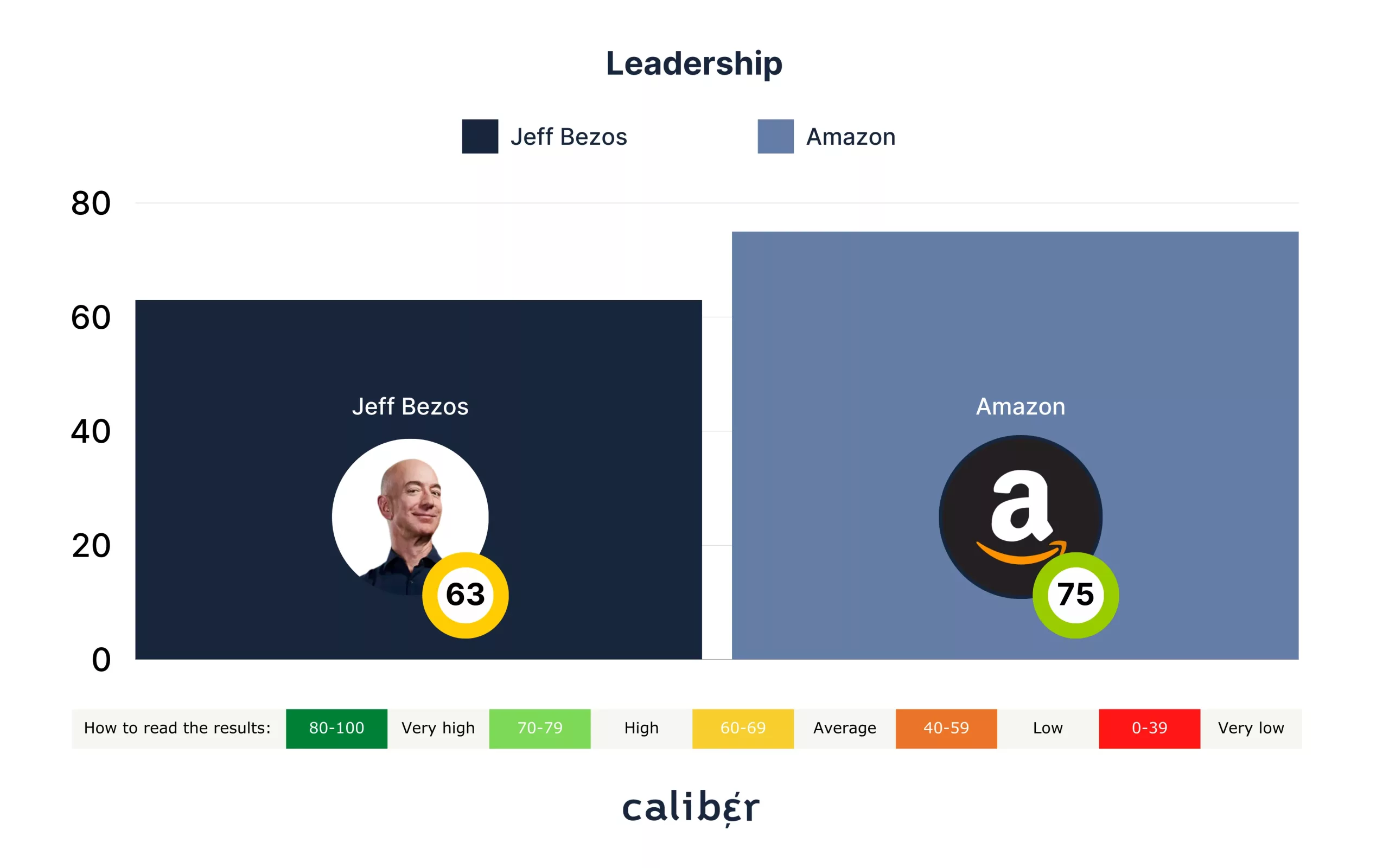

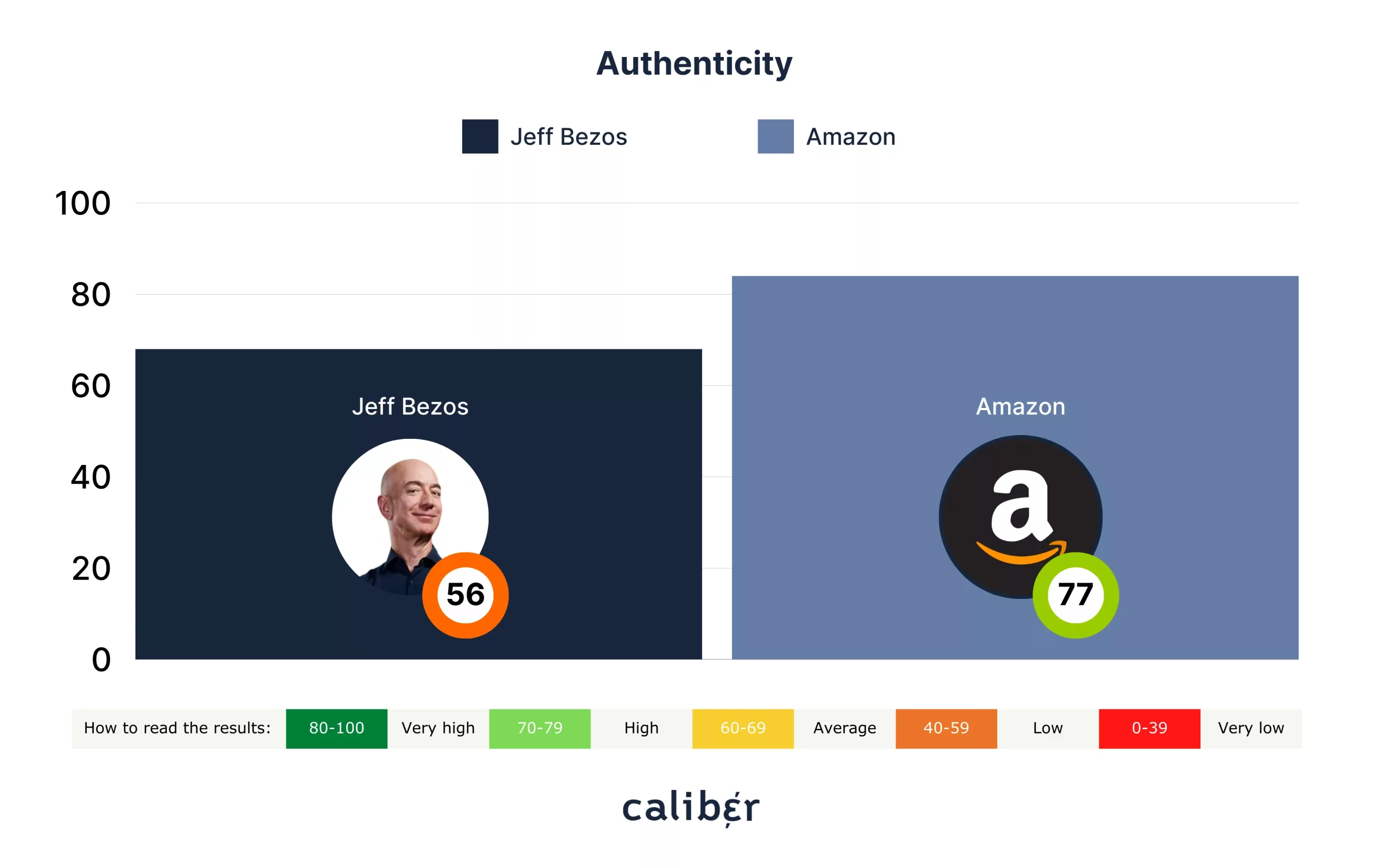

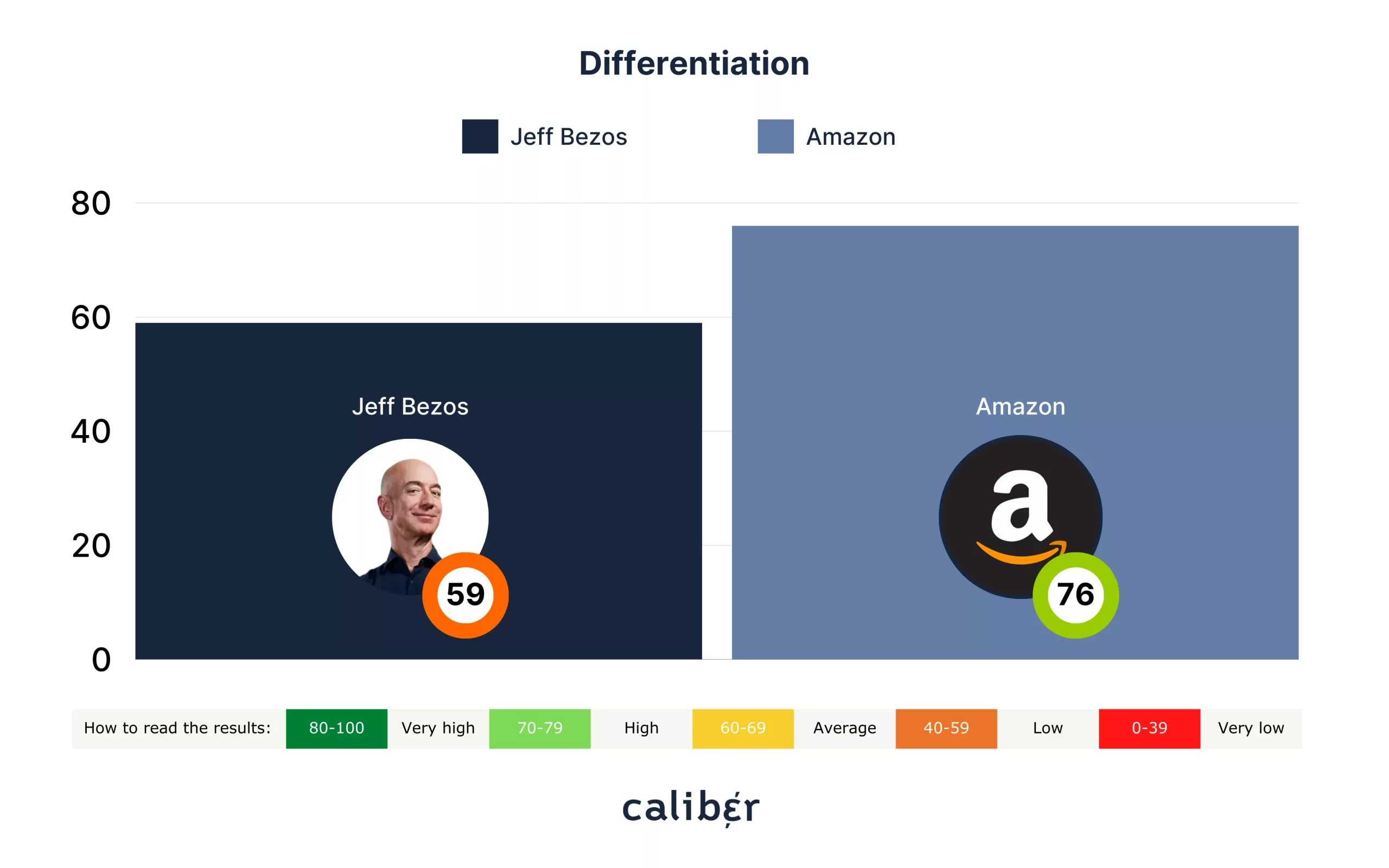

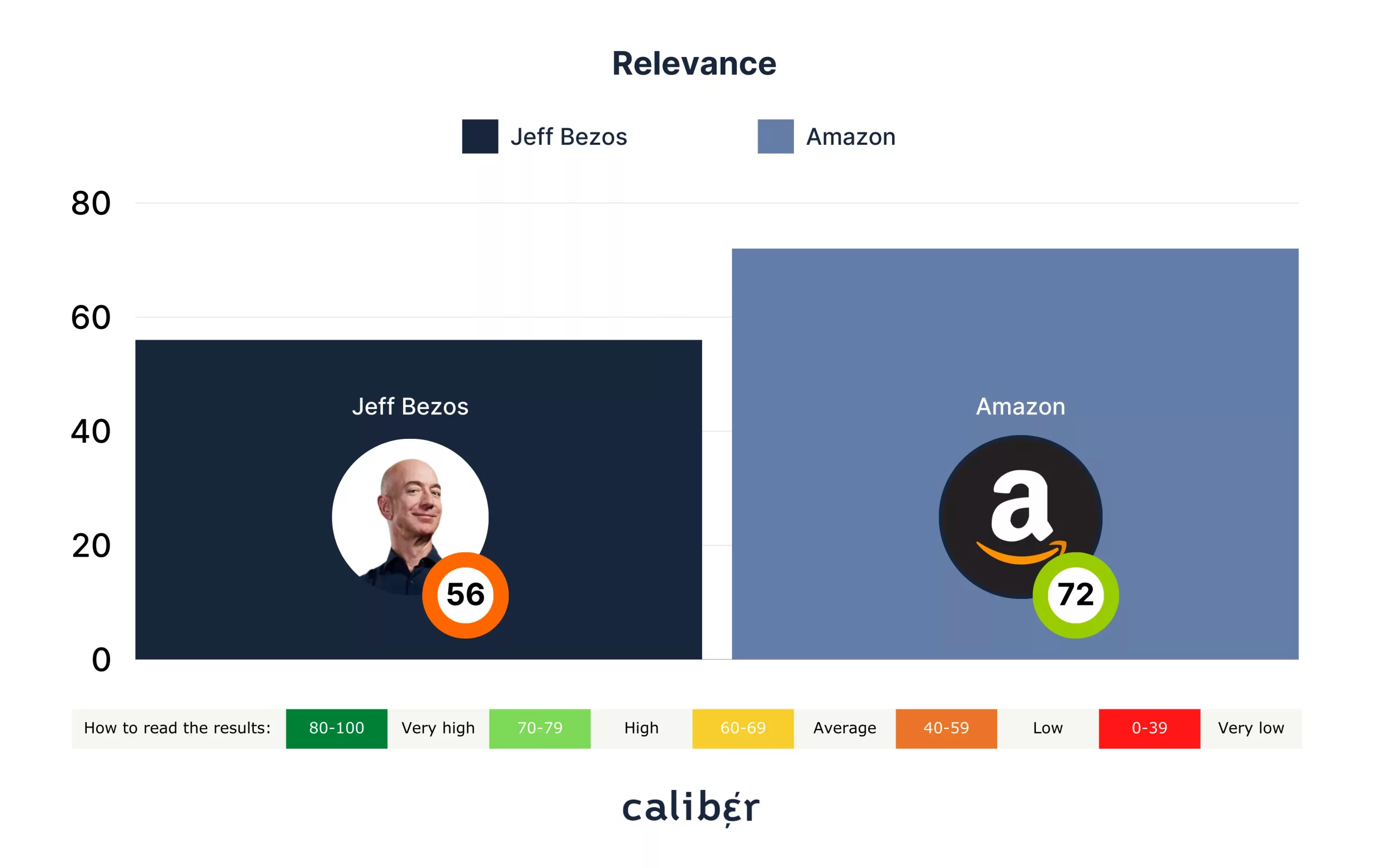

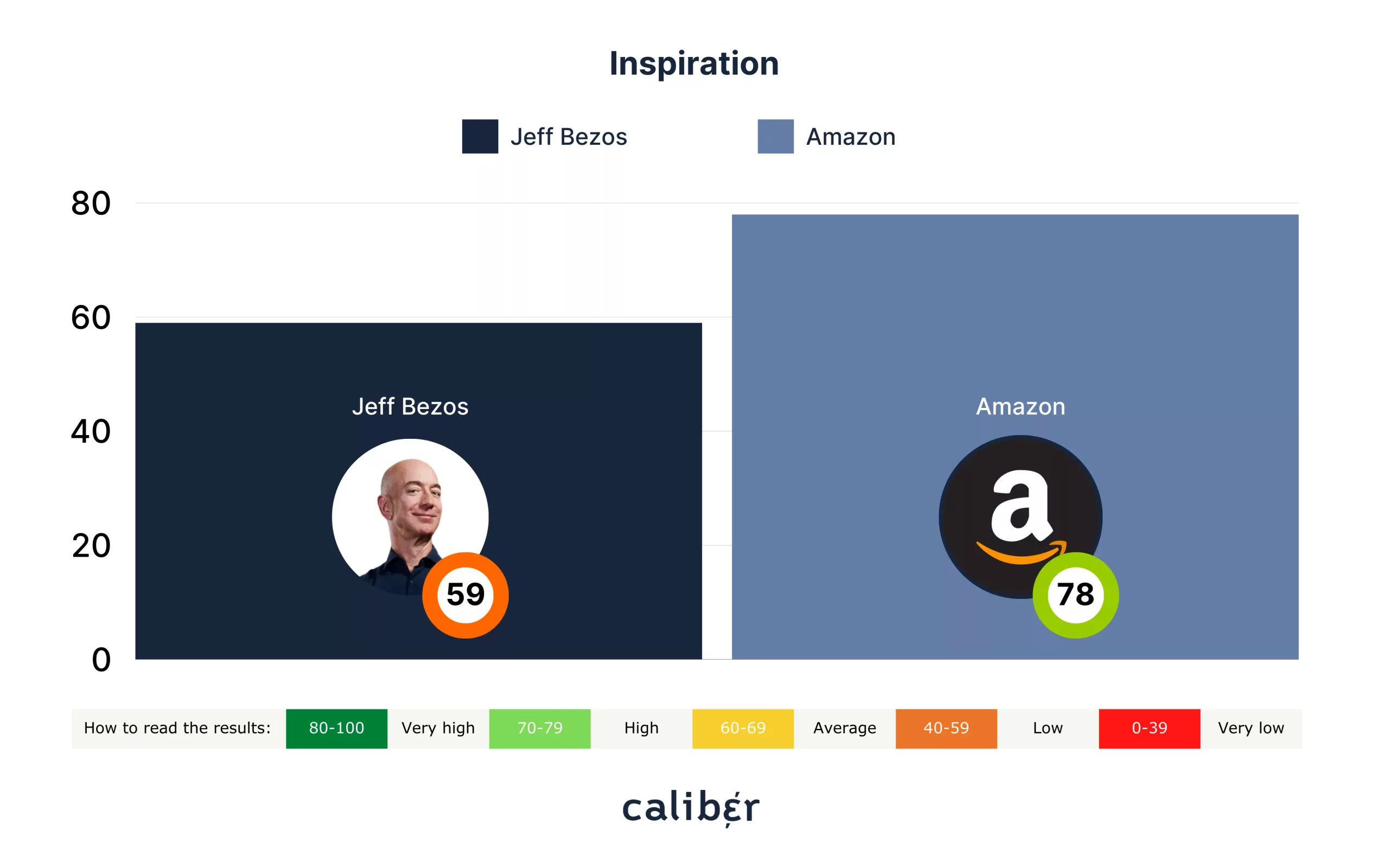

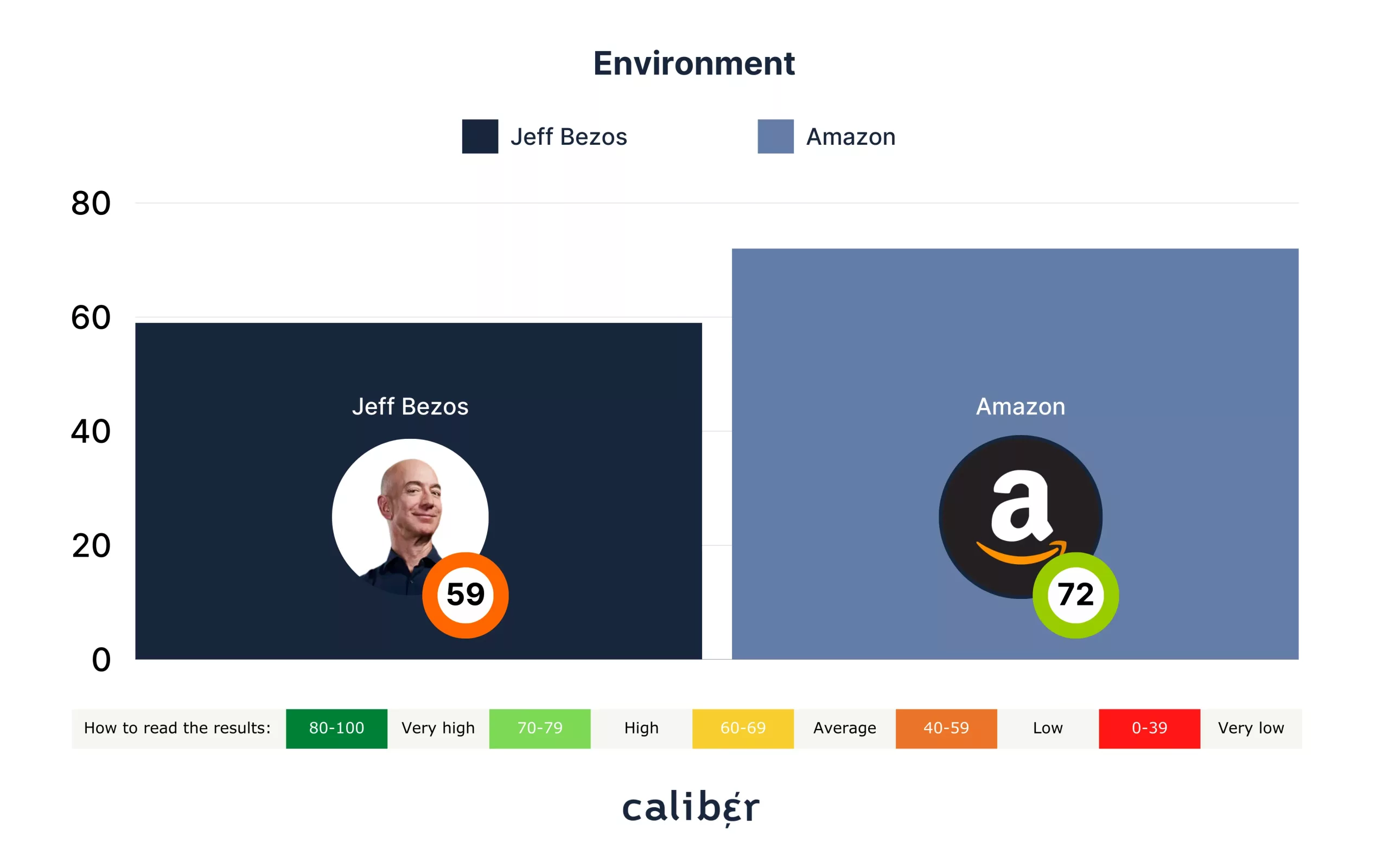

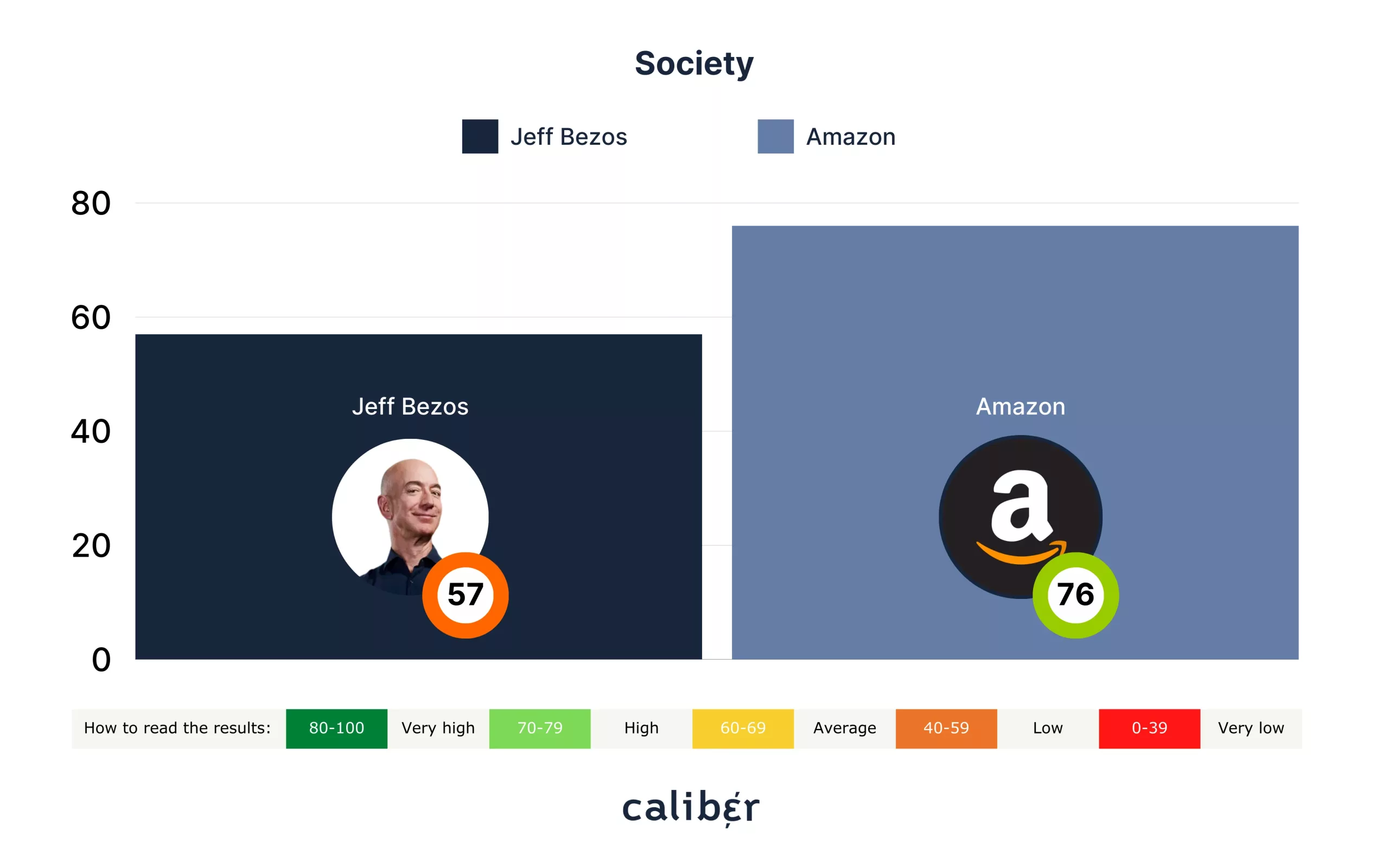

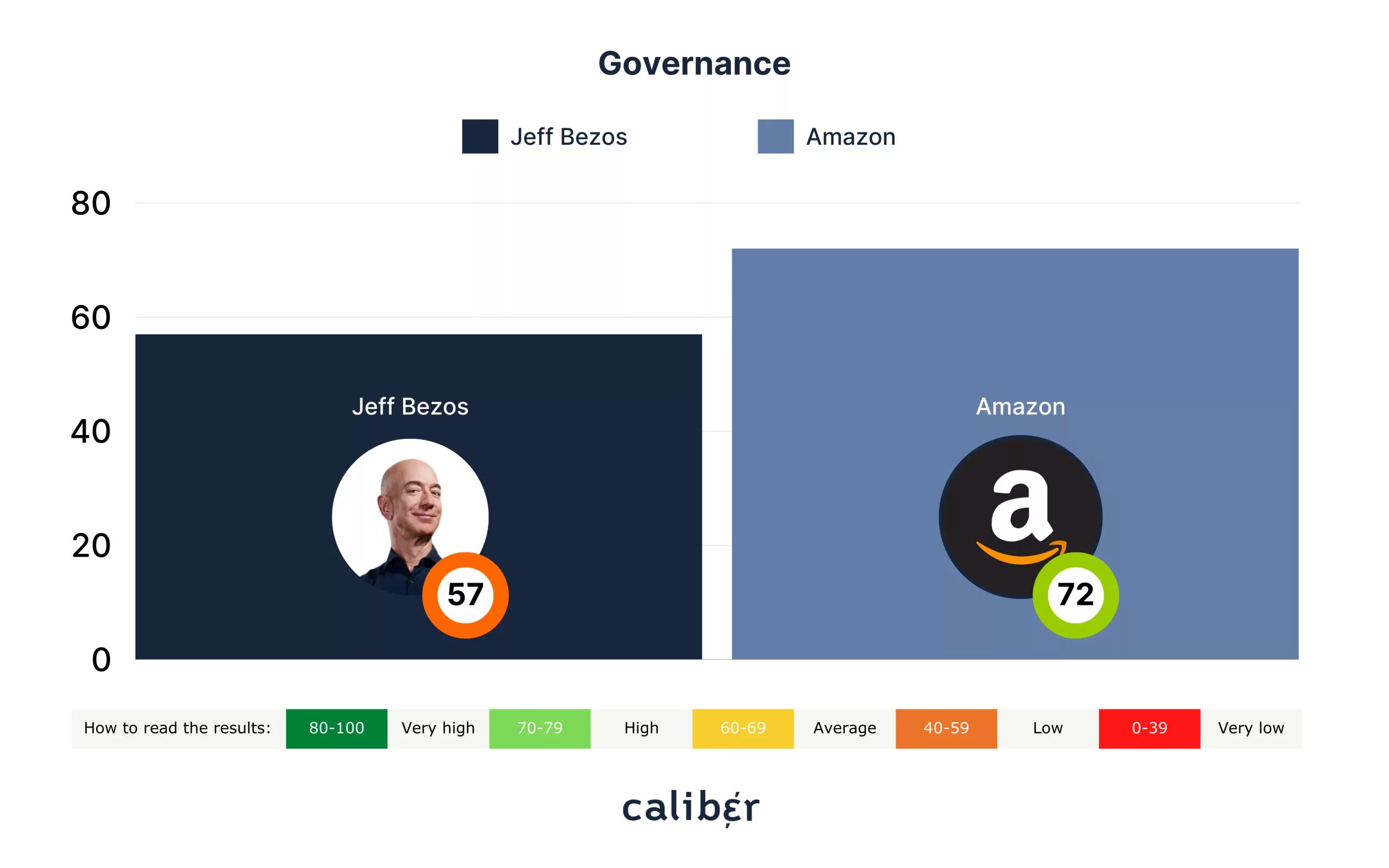

Finally, let’s turn to Jeff Bezos, who has a much worse reputation than Amazon, the company he founded and ran until 2021.

In fact, his brand and reputation scores are much lower than Amazon’s across every attribute.

One takeaway from this data is that visible leaders may do more harm than good to their company’s reputation. Indeed, it’s a far cry from the days of Virgin’s Richard Branson and Apple’s Steve Jobs, whose love of the limelight did wonders for their public personas and their companies’ reputations.

Our results show this is no longer the case: the most widely identified CEOs (Musk and Zuckerberg) both have very low Trust & Like Scores — and their associated companies also suffer from a relatively bad reputation.

Of course, these corporate reputations might not result from their leaders’ personal reputations, but one can easily argue that their visibility certainly doesn’t help. Indeed, the recent decline of Twitter/X’s Trust & Like Score suggests the existence of a “Musk effect”.

Then again, none of this may matter much to X or Tesla’s stakeholders — and certainly not to Musk himself.

As Nick Hilton puts it: “Musk’s unilateral approach to decision making — anathema to American industrial practices of the past hundred years — has got him into trouble before, notably when he threatened to take Tesla private, or when he, you know, bought Twitter.

But it is also perceived as the route of his success. Take away Musk’s ability to make decisions — tough decisions, big decisions — and you will end up with a version of Elon Musk that has all of the flaws and none of the talents.”

The case of Jeff Bezos is very different — a very low personal TLS juxtaposed against a very high company TLS. What explains this contrast?

It certainly puzzled the writer of an Inc. piece called “Why Does Everyone Seem to Hate Jeff Bezos?”, which noted that while “everyone seems to like what Amazon offers: an easy way to get the stuff you need”, its founder and executive chairman “irritates just about everyone” — though the writer drew a blank as to why.

In our view, the result may be explained by the fact that while Zuckerberg’s and Musk’s visibility is more controversial (socially and politically) and directly connected to the companies they own and lead, Bezos’s is less controversial — and less connected to Amazon (like his multi-billion-dollar divorce).

Like everything in America, how corporate leaders are perceived is political, too. Just look at the numbers below comparing how Democrats and Republicans rate Musk, Zuckerberg, and Bezos across a selection of attributes and how likely they’d be to recommend a company led by each man if given the chance.

As these figures show, Republicans overwhelmingly “prefer” the bigwigs of Amazon and Tesla (and owner of X), whereas Mark Zuckerberg has a better reputation among Democrats.

So, does this data further make the case for “CEO invisibility”? In a way, yes. Taken together, the data suggests that leaders with strong personal brands are risky, especially leaders whose brand and reputation divide stakeholders down political lines.

Far better, too, to have a bland leader than one capable of taking down the company with a misjudged tweet.

Questioning whether the age of the “Brand CEO” was over, Hilton concluded: “Humans are flighty, subject to change, error or illness.

Brands, on the other hand, are far more resilient. Coca-Cola cannot decide it wants to go travelling for a year. Jaguar Land Rover won’t randomly use a racial slur at a gala. Lego isn’t going to come down with a debilitating case of Seasonal Affective Disorder.”

In conclusion, then, as the CEO, chairman or founder of a leading company, it’s probably best to keep a low profile from a reputation perspective — and if you do boost your visibility, it’s best to avoid any controversy and to keep your company out of it as well.

Our recent Perception Brief illuminated the three hot-button issues that companies in America are on relatively safe ground addressing — and the ones that could be reputational minefields.

High-profile corporate leaders should probably be even more circumspect.

* We surveyed 852 respondents in the United States between 4 and 15 December 2023.

** Below is our standard terminology when asking respondents to rate companies on various brand and reputation attributes. We modified the language accordingly when asking respondents about individuals.

All questions are asked on a 1–7 Likert scale. Responses are normalized into a rating scale of 0–100.

Offering – COMPANY offers compelling products and services

Innovation – COMPANY is innovative in its field

Integrity – COMPANY behaves responsibly

Leadership – COMPANY demonstrates leadership

Advocacy – I would say something positive about COMPANY to others, if given the chance

Consideration – I would buy, or continue buying, products and services from COMPANY, if given the chance

Recommendation – I would recommend COMPANY to others, if given the chance

Employment – If I were looking for a job, I would consider COMPANY as a place to work

Authenticity – COMPANY is a company that does what is says

Differentiation – I consider COMPANY to stand out from the competition in a positive way

Relevance – I can relate to what COMPANY stands for

Inspiration – I find COMPANY interesting

Environment COMPANY has a positive impact on the planet.

Society COMPANY has a positive impact on people and society.

Governance COMPANY is ethical in the way it conducts business.

© 2024 Group Caliber | All Rights Reserved | VAT: DK39314320